episode known as the Dirty War.

episode known as the Dirty War.Calling something a war, even a "dirty" war implies that it is a struggle with at least two sides. In Argentina that would be a bit misleading. Before Videla and his gang took over Argentina, the country was indeed in a state of near civil war. Leftist guerrillas had embarked on an armed revolutionary struggle and the state security apparatus responded in kind; levels of violence escalated alarmingly. Then in 1976 Videla, the army's commander in chief, overthrew the civilian government of President Isabél Peron and gave his uniformed pals a completely free hand to

crush the insurgents.

crush the insurgents. "As many people as is necessary will die in Argentina to protect the hemisphere from the international communist conspiracy", Mr Videla had said in 1975. Once in power, he proved as good as his word. The armed forces instituted a reign of terror against the actual guerrillas, but they also targeted anyone who might be assisting them or who had dangerous left wing ideas or who just looked funny. The regime moved beyond combating the rebels (who were soon

crushed) to trying to exterminate Argentina's left.

crushed) to trying to exterminate Argentina's left.To make it harder for friends and relatives of the murdered to bring troubling court cases against the regime, Videla's cronies made their victims disappear. One trick was to drug captives and then throw them out of airplanes into the south Atlantic. On the off-chance that any of the corpses were washed ashore, the drugged victims were stripped naked to remove anything that might identify them.

Videla and his accomplices were amnestied during Argentina's transition to democracy, but gradually the law caught up

with him. In 1998 he was forced to stand trial for the "appropriation of minors" - the kidnapping of the children of the disappeared for illegal adoption by army officers and others sympathetic to the military regime. Then in 2007 the general Dirty War amnesty was overthrown by the courts; in 2010 he received a life sentence for the torture and murder of 31 victims of the military regime. He died in prison.

with him. In 1998 he was forced to stand trial for the "appropriation of minors" - the kidnapping of the children of the disappeared for illegal adoption by army officers and others sympathetic to the military regime. Then in 2007 the general Dirty War amnesty was overthrown by the courts; in 2010 he received a life sentence for the torture and murder of 31 victims of the military regime. He died in prison.It is easy to focus on sinister figures like Videla and reduce their victims to a faceless mass - with 30,000 people killed by Videla, it can be hard to remember that they all had names, friends, a life, ambitions and

dreams that were brutally cut short. El Proyecto Desaparecidos attempts to humanise this victims, posting photographs and brief biographies of the killed.

dreams that were brutally cut short. El Proyecto Desaparecidos attempts to humanise this victims, posting photographs and brief biographies of the killed. One of the more heartbreaking parts of El Proyecto Desaparecidos' website is the Wall of Memory - face after face of those killed by Argentina's army, with links to a summary of their life and what is known of their fate.

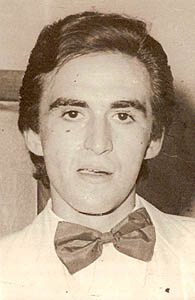

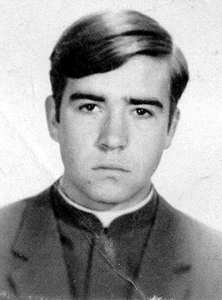

Some random victims:

Silvia de Raffaelli de Parejo - 28 years old when she was abducted from her home and never seen again.

Alicia Eguren de Cooke - a writer, poet and political activist who was 52 years old when she was thrown from a helicopter into the River Plate.

Juan Carlos Galván - a 24 years old artist who taken from his widowed mother's home and never seen again.

Oscar Luis Hodola & Sirena Acuña - 28 and 26 when they were taken away from their son.

More:

Jorge Rafaél Videla obituary (Guardian)

Argentina ex-military leader Jorge Rafael Videla dies (BBC)

Painful search for Argentina's disappeared (BBC)

Argentina marks 'Night of the Pencils' (BBC) An account of the abduction, torture and murder of left wing secondary school students.

Project Disappeared (in English)

El Proyecto Desaparecidos (in Spanish)

The Wall of Memory