Dien Bien Phu was an odd location for the decisive battle that would end a war. It was located far from major population centres in the north west of Vietnam, near the border with Laos. It only became the site of a major battle because the French chose to send a large force there. By 1953 their position in Indochina was deteriorating. The French commander, General Henri Navarre, decided to establish a fortified base in Dien Bien Phu for two reasons. Firstly, the hope was that a strong force there would be able to block the supply of arms from China through Vietnam to communist rebels in Laos. The more ambitious hope, though, was that the Vietnamese rebels would choose to deploy a large force to attack Dien Bien Phu, a force that could then be destroyed by the better armed and trained French forces.

Dien Bien Phu was so remote that it could only be supplied from the air, but this was not seen as a problem. There was an old airstrip there from the Second World War that the French would be able to use to fly in supplies and evacuate the wounded. French paratroopers secured the runway on the 20th November 1953 and then more troops and heavy equipment were flown in, including a number of light tanks. A series of forts were established in the surrounding area. The French commander at Dien Bien Phu was Colonel de Castries, a French cavalry commander who looked forward to the showdown with the Vietnamese rebels. All told he had some 16,000 men under him.

The political leader of the rebels was the famous Ho Chi Minh, but the military commander was Vo Nguyen Giap. Giap decided to accept the challenge posed by Dien Bien Phu and moved a 50,000 strong force to invest the defenders. By the end of January the first clashes between the two armies had occurred, but it was only on the 13th of March that the battle erupted in earnest. The rebels had dug in artillery in bunkers overlooking one of the French forts. After a devastating bombardment the Vietnamese stormed the fort with a mass infantry assault. The French artillery commander was so shocked by his inability to counter the Vietnamese guns that he blew himself up with a hand grenade.

On the next day the rebels overran another fort in the same manner as the first Now they could pore artillery fire down on the airstrip, rendering it useless for the French defenders. The French could still haphazardly receive supplies dropped by parachute, but there was no way out for their wounded. The garrison was now trapped.

Thereafter the battle progressed more like something from the First World War than the kind of mobile fighting the French had hoped for. Shelling and infantry assaults gradually forced the French back into an ever smaller area. The fighting was not all one-sided - in bold counter-attacks the defenders sometimes recovered lost positions. The suffering on both sides was horrendous. But without use of the runway for the French there could only be one eventual outcome.

Thereafter the battle progressed more like something from the First World War than the kind of mobile fighting the French had hoped for. Shelling and infantry assaults gradually forced the French back into an ever smaller area. The fighting was not all one-sided - in bold counter-attacks the defenders sometimes recovered lost positions. The suffering on both sides was horrendous. But without use of the runway for the French there could only be one eventual outcome.As the situation became more desperate, the United States stepped up its material aid for the French in Indochina, but avoided overt direct involvement. There were some in leadership positions who wanted to commit significant American forces to help the French; there are even suggestions that the Americans proposed to use nuclear weapons to break the siege or to give them to the French for this, but this has never been definitively established. In the end those who favoured non-intervention won out, and the Americans left Dien Bien Phu to its fate.

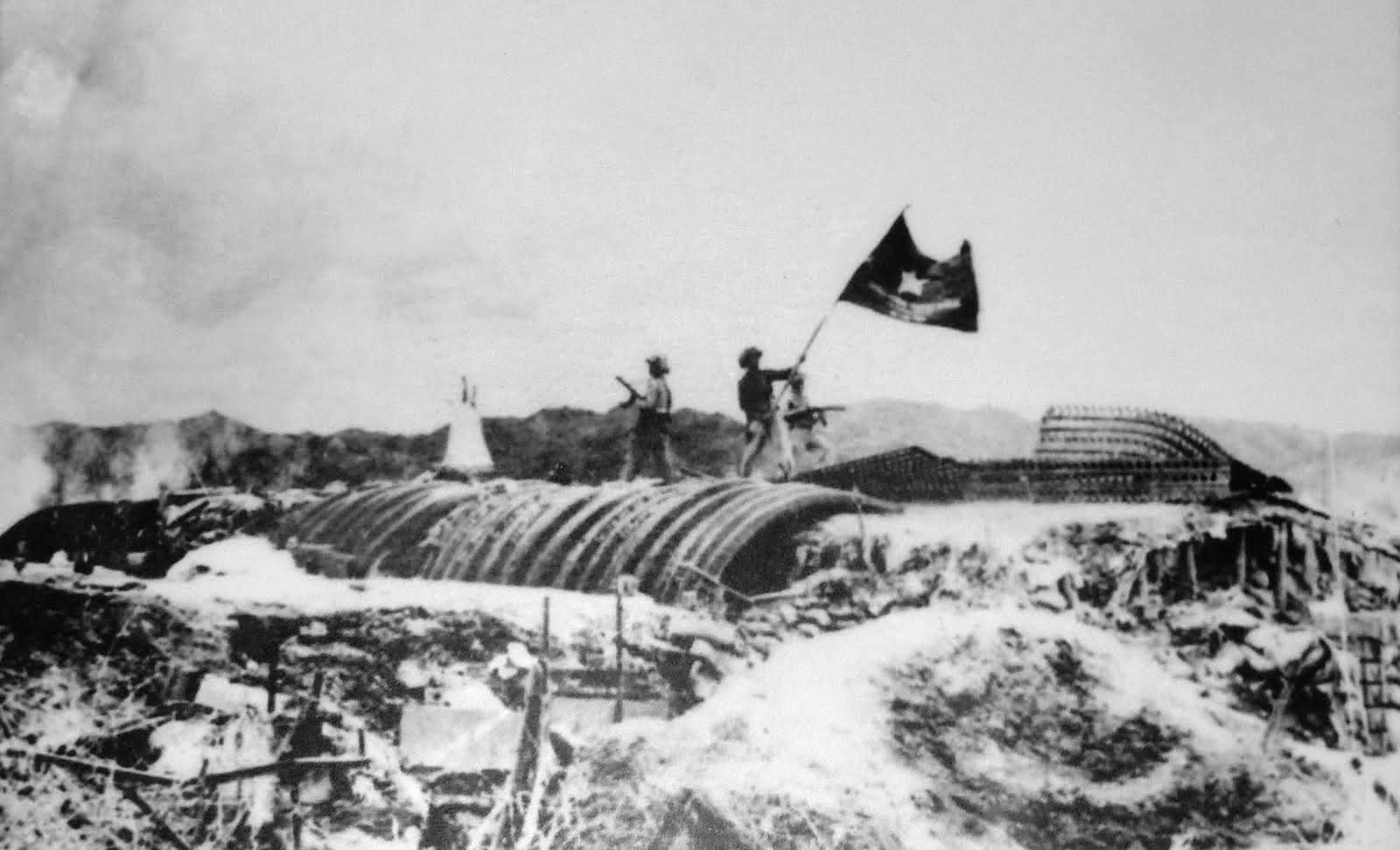

The end came on the 7th of May. By then the French defenders were shattered and isolated. Giap ordered an all-out attack to bring the battle to an end. In his last radio broadcast to his commander, de Castries recounted the desperate situation in which the garrison found itself and was ordered to fight on till the very end. By nightfall the battle was over, with all the French positions overrun. The surviving defenders were led off into captivity.

As well as the captured male soldiers, the French prisoners included one French woman, the nurse Geneviève de Galard, who had been trapped when the runway became unusable. Also captured were the Algerian and Vietnamese women who worked in the two bordels mobiles de campagne serving the garrison. Some 3,290 French troops were eventually repatriated, together with Ms de Galard. The Vietnamese sex workers were apparently sent off somewhere for re-education. The eventual fate of the Vietnamese loyalists who fought on the French side is mysterious.

For the Vietnamese the battle was a triumph, albeit one bought at terrible cost. The rebels had gone in a few short years from waging a guerrilla war to being able to take on a first world army in conventional battle. For France, Dien Bien Phu was a disaster. They had chosen the ground and invited the rebels to fight them and then had been comprehensively defeated. But the defeat did not end France's colonial pretensions. While the French were soon after to quit Indochina, the debacle hardened the resolve of the military to fight on against the nationalist rebels in Algeria, in the hope that some kind of victory there would restore their honour.

By coincidence, a conference to end the Indochina War opened in Geneva the day after the fall of Dien Bien Phu. The conference saw Vietnam partitioned into a northern zone under Ho Chi Minh and southern Republic of Vietnam supported by France (and subsequently the USA). Elections in 1956 were meant to reunite the two parts of the country, though events unfolded otherwise.

More:

The Battle of Dien Bien Phu (Wikipedia)

Dien Bien Phu: Did the US offer France an A-bomb? (BBC News)

The Siege of Dien Bien Phu (BBC Radio 4 documentary)