In the near future the United Nations will receive an application for membership from a new country – the country of Palestine. The bid for UN membership is being made by the group surrounding Mahmoud Abbas, the president of the Palestinian Authority and the Chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organisation. Their proposal is to create a Palestinian state on those parts of historic Palestine that were not occupied by Israel until 1967 – that is, the territories we know as the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, which includes all of East Jerusalem.

Abbas is pursuing this strategy despite opposition from the United States and Israel, who are both exercising considerable pressure on him to not go down this road. They are offering him negotiations, without preconditions, but Abbas and his circle feel that negotiations have failed and that talks brokered by the USA will continue to go nowhere. In this they are probably correct. The Israeli government likes negotiations because it can spin them out indefinitely, grabbing ever more Palestinian land in the meantime. And the USA, far from being some kind of honest broker, has used negotiations in the past to try and cajole the Palestinians into some kind of grossly inequitable settlement. Abbas hopes that by taking the Palestinian case to the UN he can internationalise the conflict and change the dynamic. In advance of formally applying for UN membership, Abbas' government has tried to build up its administration of the West Bank areas it runs so that it looks like a credible government in waiting.

Not all Palestinians and friends of Palestinians are in favour of the bid for UN membership. For some, the Abbas government has so little credibility left that any initiative it undertakes is intrinsically suspect. Many Palestinians suspect that the bid, successful or not, will make no difference to their lives. And many think that attempting to create a Palestinian state in Gaza and the West Bank risks abandoning the interests of Palestinians elsewhere – those in exile across the world and those living as second class citizens within pre-1967 Israel.

Still, Israel's vehement hostility to the bid has somewhat rallied pro-Palestinian support behind it. The Israeli state has a number of reasons for opposing the bid. One of these is that the status quo suits it very well, as the Israeli state and its settlers can continue gobbling up Palestinian land. There is also some fear that recognition of a Palestinian state would make it easier for Israeli army officers and politicians to be referred to the International Criminal Court. And a further fear is that if the UN recognises a Palestinian state in all of Gaza and the West Bank, it will not be possible to bully the Palestinian leadership into accepting the far more runty faux state that the Israeli government have in mind for them.

The Israelis have put considerable diplomatic efforts into trying to block Palestinian membership at the UN, but they know that there is overwhelming support in the chancelleries of the world for the proposal. The only way the Palestinian bid can realistically be blocked is by a Security Council veto by the USA. This of course puts the USA in an awkward position. The USA always blocks Security Council motions that are unacceptable to Israel, but in this case there is such overwhelming support for the motion that it will look completely out of step with world opinion if it backs its little friend. Worse, a US veto will destroy any latent credibility the superpower has in the now democratising Arab world. Barack Obama spoke earlier this year of his wish to see a Palestinian state emerging in Gaza and the West Bank – he would look like a complete flubblehead if the USA were to veto a proposal to create just such a state.

The USA is therefore very keen not to have to use its veto, and has been pressurising the Palestinians to not go ahead with their UN membership bid. But Abbas seems to be determined to go ahead, as the Americans are not offering him anything credible. The likelihood is then that the USA will veto Palestinian membership of the UN in the Security Council, taking the ghastly negative consequences that this would involve.

The expectation is that the Palestinians will then take their case to the General Assembly. The General Assembly cannot vote to allow a country to join the United Nations, but it can give enhanced observer status to the Palestinians. This is what is expected to happen. The Palestinians will then be able to engage more fully with UN agencies and may achieve easier access to the International Criminal Court that so worries Israeli war criminals.

After that, anything could happen. US parliamentarians have threatened to cut funds to the Palestinian Authority if the bid goes ahead. There is the strong possibility that the Israelis (who collect tax revenues for the PA, as a result of a bizarre feature of the Oslo Accords that set up the Authority) will also withhold funds from the Palestinian Authority. The Palestinians could therefore find themselves with a degree of diplomatic recognition but with a civil administration that is collapsing through lack of funds.

more:

Curb Your Enthusiasm: Israel and Palestine after the UN (International Crisis Group report on the Palestinian bid for UN membership; they wish people would just get along)

Ireland's call to support UN membership for Palestine [PDF] (an advertisement in today's Irish Times supporting the bid from Sadaka - the Ireland Palestine Alliance)

IPSC statement on the Palestinian “UN statehood initiative (a more ambivalent position adopted by the Ireland Palestine Solidarity Campaign)

17 September, 2011

15 September, 2011

Bahrain's Throne of Blood

When the wind of change started blowing through the Arab world earlier this year, Bahrain was one of the countries affected by unrest. In some ways this was not too surprising – like the other countries of the region, it languished under authoritarian rule, this time of a monarchical stripe. But the unrest was unusual in that it was occurring in an oil producing country, as conventional thinking on the Arab world describes countries like Bahrain – oil producers with a relatively small population – as rentier states. The government earns its money from oil production, so it does not have to tax its people and concede the political participation they might look for in return. Furthermore, oil revenue gives regimes the monies to buy off potential opposition.

But Bahrain still saw considerable unrest. This might be because of its own unique features – it is a Shia Muslim majority country with a Sunni Muslim monarch who has been careful to exclude Shia Muslims from positions of power. This blatant unfairness cannot but have triggered resentment that then erupted when the Arab masses were vitalised by the emerging Arab Spring. Yet the unrest in Bahrain does not seem to have had a particularly sectarian quality*, with both Sunni and Shia Muslims all taking to the streets and looking for freedom.

Sadly, the king of Bahrain has been able to crush the rebellion of his people, at least for now. Several factors allowed him to succeed where Mubarak, Ben Ali, and now Qaddafi failed. One of these was the oil wealth that came the king's way, which had allowed him to build up a mercenary army of thugs from around the Arab world. These people could be relied on to fire on Bahraini protesters because they would not be worrying that the people they were killing could be their friends and relations. The king also had the support of Saudi Arabia, which sent in its own army to help crush the protests; the Saudi rulers were obviously keen to prevent Bahraini protesters succeeding and encouraging their people to follow their example. And the king benefited from the tacit support of the USA and its allies. A US fleet is based in Bahrain, and any democratic transition there might have sent it packing. The Americans also feared that a democratic Bahrain might move into the orbit of Iran.

Since the democracy movement was crushed, Bahrain has been enduring a reign of terror, with protesters and activists rounded up and subjected to torture before receiving long prison sentences in kangaroo courts. This has all happened largely away from the attention of the world, as dramatic and more photogenic events in other countries have taken over the news cycles. That the unrest was crushed relatively quickly has probably also played to the advantage of the king, saving him from the kind of ongoing travails that the Syrian regime is continuing to endure.

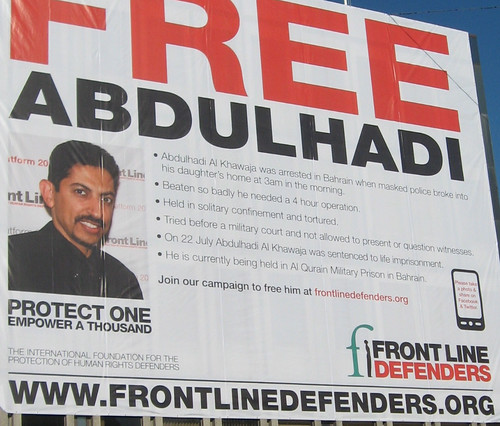

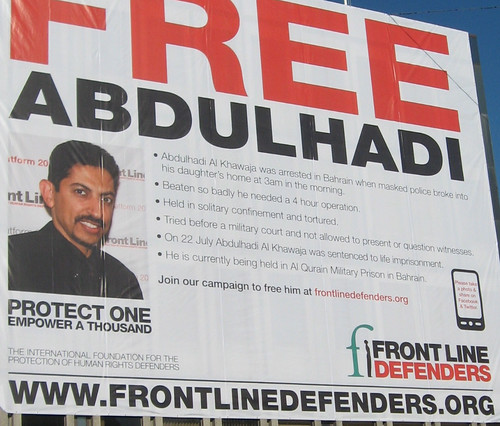

In my own country, the involvement of a prestigious medical school here in the education of Bahraini doctors has somewhat kept the Bahraini crisis in the public eye. Although the medical school has largely washed its hands of the crisis, some doctors in Ireland have campaigned to publicise the fate of doctors in Bahrain who have found themselves facing the wrong end of the regime after they took part in protests or simply gave medical treatment to people the regime's thugs had injured. The Front Line Defenders organisation has also tried to keep Bahrain in the spotlight, placing enormous posters in central Dublin concerning the arrest, torture, and detention of human rights defenders in Bahrain like Abdulhadi Al-Khawaja.

It's hard to know what will happen in Bahrain. At the moment, the Arab Spring looks like it has to some extent run out of steam across the region generally. However, this may be a false impression – away from Libya, Egypt, and Tunisia the dictators and kings may think they have things there way, but they could soon be facing another wave of freedom. Hopefully this will see the region's brutal rulers, including Bahrain's tyrant king, swept away to the dustbin of history.

*I am open to correction on this point.

But Bahrain still saw considerable unrest. This might be because of its own unique features – it is a Shia Muslim majority country with a Sunni Muslim monarch who has been careful to exclude Shia Muslims from positions of power. This blatant unfairness cannot but have triggered resentment that then erupted when the Arab masses were vitalised by the emerging Arab Spring. Yet the unrest in Bahrain does not seem to have had a particularly sectarian quality*, with both Sunni and Shia Muslims all taking to the streets and looking for freedom.

Sadly, the king of Bahrain has been able to crush the rebellion of his people, at least for now. Several factors allowed him to succeed where Mubarak, Ben Ali, and now Qaddafi failed. One of these was the oil wealth that came the king's way, which had allowed him to build up a mercenary army of thugs from around the Arab world. These people could be relied on to fire on Bahraini protesters because they would not be worrying that the people they were killing could be their friends and relations. The king also had the support of Saudi Arabia, which sent in its own army to help crush the protests; the Saudi rulers were obviously keen to prevent Bahraini protesters succeeding and encouraging their people to follow their example. And the king benefited from the tacit support of the USA and its allies. A US fleet is based in Bahrain, and any democratic transition there might have sent it packing. The Americans also feared that a democratic Bahrain might move into the orbit of Iran.

Since the democracy movement was crushed, Bahrain has been enduring a reign of terror, with protesters and activists rounded up and subjected to torture before receiving long prison sentences in kangaroo courts. This has all happened largely away from the attention of the world, as dramatic and more photogenic events in other countries have taken over the news cycles. That the unrest was crushed relatively quickly has probably also played to the advantage of the king, saving him from the kind of ongoing travails that the Syrian regime is continuing to endure.

In my own country, the involvement of a prestigious medical school here in the education of Bahraini doctors has somewhat kept the Bahraini crisis in the public eye. Although the medical school has largely washed its hands of the crisis, some doctors in Ireland have campaigned to publicise the fate of doctors in Bahrain who have found themselves facing the wrong end of the regime after they took part in protests or simply gave medical treatment to people the regime's thugs had injured. The Front Line Defenders organisation has also tried to keep Bahrain in the spotlight, placing enormous posters in central Dublin concerning the arrest, torture, and detention of human rights defenders in Bahrain like Abdulhadi Al-Khawaja.

It's hard to know what will happen in Bahrain. At the moment, the Arab Spring looks like it has to some extent run out of steam across the region generally. However, this may be a false impression – away from Libya, Egypt, and Tunisia the dictators and kings may think they have things there way, but they could soon be facing another wave of freedom. Hopefully this will see the region's brutal rulers, including Bahrain's tyrant king, swept away to the dustbin of history.

*I am open to correction on this point.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)