I have been thinking for a while about maybe doing a thesis on the relationship between the president and prime minister of the Palestinian Authority, going back to the period when Abbas was appointed as prime minister to Arafat's president. I could do some kind of comparative analysis based on the literature on other semi-presidential polities and make observations on how the office-holders have or have not managed to leverage the power of their offices.

I have been thinking for a while about maybe doing a thesis on the relationship between the president and prime minister of the Palestinian Authority, going back to the period when Abbas was appointed as prime minister to Arafat's president. I could do some kind of comparative analysis based on the literature on other semi-presidential polities and make observations on how the office-holders have or have not managed to leverage the power of their offices. Having come up with this vague idea some time ago, I then got a bit bored with it, and started thinking if there is a so-what quality to the relationship between two offices in a non-state that governs no territory and is in any case on the brink of collapse. It seems maybe a bit like doing research on the deck-chair arrangement patterns on the Titanic as compared to those favoured on other cruise liners, to get all analogical.

The topic has started to interest me a bit more recently, as the tensions between Hamas and Fatah have escalated

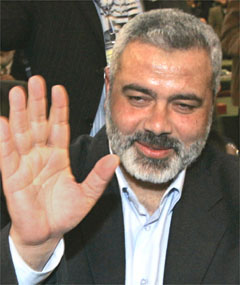

(as you know, the Palestinian prime minister is from Hamas and the president from Fatah). Last week there was the ghoulish episode of a prominent Fatah leader's children being murdered by gunmen outside their school. On Thursday, there seems to have been an attempt on the life of Ismail Haniyeh, the prime minister, with Haniyeh publicly accusing the senior Fatah figure Mohammed Dahlan of ordering the attack. Today President Mahmoud Abbas has called for joint elections to the parliament and presidency to resolve the political deadlock. Presumably he is assuming that in simultanaeous election the same side will win both elections, and hoping that he has the prestige to win these elections.

(as you know, the Palestinian prime minister is from Hamas and the president from Fatah). Last week there was the ghoulish episode of a prominent Fatah leader's children being murdered by gunmen outside their school. On Thursday, there seems to have been an attempt on the life of Ismail Haniyeh, the prime minister, with Haniyeh publicly accusing the senior Fatah figure Mohammed Dahlan of ordering the attack. Today President Mahmoud Abbas has called for joint elections to the parliament and presidency to resolve the political deadlock. Presumably he is assuming that in simultanaeous election the same side will win both elections, and hoping that he has the prestige to win these elections.So - it is like the internal politics of the Palestinians, and the struggle between the competing legitimacies of the parliament and president is actually important to what is going on, with the failure to reconcile the prerogatives of the presidential and prime-ministerial offices a key driver of the malaise of Palestinian politics. Maybe it is time to dig up those books on semi-presidentialism.