When I was in Spy School, I became interested in the Christian communities of the Middle East. People tend to think of Arab countries as being uniformly Muslim, forgetting that these places are often home to quite large non-Muslim minorities, many of whom are Christian. Egypt, Palestine, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq all have significant communities of indigenous Christians, which have managed to co-exist with their Muslim neighbours.

I began to think about writing my thesis on Middle Eastern Christians, with a particular focus on the Christian Palestinian community (or communities). I was interested in how they relate to the wider Palestinian community, in a time when the Palestinian struggle is increasingly cast not in nationalist but in (Muslim) religious terms. I was curious as to whether that kind of narrative effectively excludes Christians from the Palestinian struggle, or whether the likes of Hamas have been able to seriously engage with their Christian co-nationals.

I left behind that potential topic partly because I was unable to narrow it down into a question that could be easily answered. Instead, I wrote about the fascinating subject of Palestinian semi-presidentialism. I nevertheless remain interested in the Middle East's religious minorities, and hope to eventually read myself into the subject.

One often recommended book on Middle Eastern Christians is From The Holy Mountain, by William Dalrymple. I have not read it myself, and I get the impression that this is more travel-writey than more scholarly works of his such as The Last Mughal or The White Mughals, but I gather it is nevertheless a fascinating portrait of Christian communities whose continued existence has become increasingly problematic.

Dalrymple himself is coming to Dublin to speak on the subject of Eastern Christians. He will be at the Royal Irish Academy, on evening of the 9th June. Admission is free, but I gather you need to mail them to reserve a place.

31 May, 2008

28 May, 2008

Party on, Ethiopia

Today is a national holiday in Ethiopia. It is the day on which they celebrate no longer being ruled by the Derg. "Derg" is the Amharic for "committee"; the Derg was the abbreviated name of the Coordinating Committee of the Armed Forces, Police, and Territorial Army. This body came into being during a series of army mutinies that brought an end to the imperial regime of Haile Selaise. Sadly, the Derg soon turned out to be a bunch of megalomaniac nutjobs, turning violently on their real and imagined enemies. After nearly twenty years of war, terror, and famine, they were finally overthrown in May 1991. The Derg's leader, Mengistu Haile Mariam, now lives in exile in Zimbabwe. He was on Monday sentenced to death in absentia by an Ethiopian court; I suspect he is hoping that Mugabe manages to remain in power.

While the current leaders of Ethiopia have displayed some authoritarian tendencies, they will be able to coast for a while yet on not being the Derg, and on being the people who overthrew them.

More Derg action:

Derg (Wikipedia)

The Establishment of the Derg(Library of Congress)

While the current leaders of Ethiopia have displayed some authoritarian tendencies, they will be able to coast for a while yet on not being the Derg, and on being the people who overthrew them.

More Derg action:

Derg (Wikipedia)

The Establishment of the Derg(Library of Congress)

25 May, 2008

What do I mean by "Syrian hegemony"?

An initially anonymous commenter took exception to my describing the period following the end of Lebanon's civil war as one of Syrian hegemony. Hegemony is a loaded term to some, but it is also descriptive, and I think it is merited in this case.

Just to recap, the Lebanese civil war ended largely because everyone was fed up with it. Lebanese leaders agreed a peace-deal in the Saudi Arabian town of Taif that tinkered with Lebanon's confessional power distribution, without demolishing it. Taif led to the disarmament of party militias, but those groups continuing resistance against the Israeli occupiers of South Lebanon were allowed to keep their weapons.

The period following the Taif agreement is often characterised as one in which Syria enjoyed unprecedented influence over its smaller neighbour. The last act in the civil war was, symbolically enough, the removal by Syrian forces of a self-declared president of Lebanon who had, from his little enclave in East Beirut, promised to liberate the country from the Syrian scourge. That this man is now one of the major players in the pro-Syrian opposition is one of Lebanon's great conundrums.

Beyond that, a number of factors point to the influence Syria exercised over post-Taif Lebanon. Another interesting factor of both symbolic and practical effect was the 1991 signing of a treaty of of "Brotherhood, Cooperation, and Coordination" between Lebanon and Syria. Although criticised in somewhat exaggerated terms for being a virtual Syrian annexation of the country, it did enmesh Lebanon so closely to the wishes of Damascus as to severely limit its independent room for manoeuvre.

At a less symbolic level, the post-Taif period saw Syria in a position to project hard power over the country. The presence of Syrian troops throughout most of Lebanon underscored its dependent status. While Taif and the Lebanese-Syrian treaty had envisaged the withdrawal of Syrian troops, they proved remarkably slow to leave. The Syrians were also able to maintain an extensive intelligence apparatus in Lebanon that could be used selectively against its local enemies. Now, of course, half the world runs intelligence networks in Lebanon, but the Syrians had the advantage of being able to run theirs overtly, without having to worry about the local cops or counter-intelligence feeling their collars.

The disarmament of Lebanese militias at the end of the civil war also increased the relative power position of the Syrians. This eliminated Christian militas that had occasionally caused trouble for Syrian interests (and played footsie with Syria's enemies in Israel). Syria's most reliable allies within Lebanon were able to retain their weapons. As groups engaging in resistance against the Israeli occupiers in the south, Amal and, particularly, Hezbollah remained in arms. These groups received their arms either directly from the Syrian state, or from its Iranian allies.

Throughout the 1990s, Syria reaped the benefits of its Lebanese hegemony. Hezbollah fighters continued to punish Israel in south Lebanon, eroding the Zionist enemy's reputation for invincibility in a way that allowed Syria to reap the benefits while remaining at arms length from any untoward consequences. Lebanese political leaders, meanwhile, were careful to remain in step with Syrian interests, perhaps motivated by the long-standing tendency of anti-Syrian politicians to die in mysterious car bomb explosions. It is striking that even when Syrian influence over Lebanon was unwinding, Damascus was still able to dictate a constitutional amendment to Beirut that would allow its preferred candidate to remain in office as Lebanese president.

That was the situation until recently. The turnaround of the last few years was striking and relatively abrupt. Under Hafez Assad, Syria had basically won the great game, thwarting Israeli efforts to extend influence into Lebanon and instead made the country its own client. Under Bashar Assad, Syria saw its troops and intelligence officials hounded out of the country; worse, Beirut now hosts a government no longer willing to bind itself to Syrian concerns, with Syria's local allies now all consigned to the opposition. Quite how this happened is something to which I will return.

Just to recap, the Lebanese civil war ended largely because everyone was fed up with it. Lebanese leaders agreed a peace-deal in the Saudi Arabian town of Taif that tinkered with Lebanon's confessional power distribution, without demolishing it. Taif led to the disarmament of party militias, but those groups continuing resistance against the Israeli occupiers of South Lebanon were allowed to keep their weapons.

The period following the Taif agreement is often characterised as one in which Syria enjoyed unprecedented influence over its smaller neighbour. The last act in the civil war was, symbolically enough, the removal by Syrian forces of a self-declared president of Lebanon who had, from his little enclave in East Beirut, promised to liberate the country from the Syrian scourge. That this man is now one of the major players in the pro-Syrian opposition is one of Lebanon's great conundrums.

Beyond that, a number of factors point to the influence Syria exercised over post-Taif Lebanon. Another interesting factor of both symbolic and practical effect was the 1991 signing of a treaty of of "Brotherhood, Cooperation, and Coordination" between Lebanon and Syria. Although criticised in somewhat exaggerated terms for being a virtual Syrian annexation of the country, it did enmesh Lebanon so closely to the wishes of Damascus as to severely limit its independent room for manoeuvre.

At a less symbolic level, the post-Taif period saw Syria in a position to project hard power over the country. The presence of Syrian troops throughout most of Lebanon underscored its dependent status. While Taif and the Lebanese-Syrian treaty had envisaged the withdrawal of Syrian troops, they proved remarkably slow to leave. The Syrians were also able to maintain an extensive intelligence apparatus in Lebanon that could be used selectively against its local enemies. Now, of course, half the world runs intelligence networks in Lebanon, but the Syrians had the advantage of being able to run theirs overtly, without having to worry about the local cops or counter-intelligence feeling their collars.

The disarmament of Lebanese militias at the end of the civil war also increased the relative power position of the Syrians. This eliminated Christian militas that had occasionally caused trouble for Syrian interests (and played footsie with Syria's enemies in Israel). Syria's most reliable allies within Lebanon were able to retain their weapons. As groups engaging in resistance against the Israeli occupiers in the south, Amal and, particularly, Hezbollah remained in arms. These groups received their arms either directly from the Syrian state, or from its Iranian allies.

Throughout the 1990s, Syria reaped the benefits of its Lebanese hegemony. Hezbollah fighters continued to punish Israel in south Lebanon, eroding the Zionist enemy's reputation for invincibility in a way that allowed Syria to reap the benefits while remaining at arms length from any untoward consequences. Lebanese political leaders, meanwhile, were careful to remain in step with Syrian interests, perhaps motivated by the long-standing tendency of anti-Syrian politicians to die in mysterious car bomb explosions. It is striking that even when Syrian influence over Lebanon was unwinding, Damascus was still able to dictate a constitutional amendment to Beirut that would allow its preferred candidate to remain in office as Lebanese president.

That was the situation until recently. The turnaround of the last few years was striking and relatively abrupt. Under Hafez Assad, Syria had basically won the great game, thwarting Israeli efforts to extend influence into Lebanon and instead made the country its own client. Under Bashar Assad, Syria saw its troops and intelligence officials hounded out of the country; worse, Beirut now hosts a government no longer willing to bind itself to Syrian concerns, with Syria's local allies now all consigned to the opposition. Quite how this happened is something to which I will return.

14 May, 2008

Lebanon blogs

I am finding Lebanese Political Journal fascinating reading, and would recommend it to anyone looking for something that is both a fascinating worm's eye view of current Lebanese events and something that steps back and analyses those events. However, it does so from a particular perspective (broadly pro-government and hostile to Hezbollah's uprising). For balance, I wouldn't mind reading something that dug with the other foot. Does anyone have any recommendations of Lebanese pro-Hezbollah English-language blogs?

Lebanon: friends and enemies

US President George W. Bush has spotted that the government of Lebanon is in trouble, so he has decided to "beef up" the Lebanese Army. Lebanese prime minister, Fuad Siniora, must be excited that help is coming his way, similar to that which the Palestinian Authority's president, Mahmud Abbas, received prior to the Hamas uprising in Gaza. Tony Blair might also be on his way.

Meanwhile, a blogwriting fellow called Optimussven has made an interesting post about Lebanese politician Walid Jumblatt. Jumblatt is the leader of the Progressive Socialist Party, and the de facto hereditary leader of many members of Lebanon's Druze community. Optimussven reports that Dick Cheney introduced a speech to the Washington Institute for Near East Policy by praising Jumblatt's "courageous stand [...] for freedom and democracy". How times change... my understanding is that when US troops were last stationed in Lebanon, Jumblatt's militia was one of those that did its best to kill as many of them as possible; it was of course less successful in this than the truck-bombers of proto-Hezbollah. Back then, Jumblatt was feuding with the Phalange militia of the Maronites, who were closely allied to Israel. Now Jumblatt and the Phalange are pals against the Syrian-allied Hezbollah, making him a lover of freedom and democracy.

Meanwhile, a blogwriting fellow called Optimussven has made an interesting post about Lebanese politician Walid Jumblatt. Jumblatt is the leader of the Progressive Socialist Party, and the de facto hereditary leader of many members of Lebanon's Druze community. Optimussven reports that Dick Cheney introduced a speech to the Washington Institute for Near East Policy by praising Jumblatt's "courageous stand [...] for freedom and democracy". How times change... my understanding is that when US troops were last stationed in Lebanon, Jumblatt's militia was one of those that did its best to kill as many of them as possible; it was of course less successful in this than the truck-bombers of proto-Hezbollah. Back then, Jumblatt was feuding with the Phalange militia of the Maronites, who were closely allied to Israel. Now Jumblatt and the Phalange are pals against the Syrian-allied Hezbollah, making him a lover of freedom and democracy.

12 May, 2008

Pakistani Judges, part two

In an earlier post I mentioned tensions within the Pakistani government on the reinstatement of judges sacked last year by President Musharraf (see: Pakistani Judges). Now the BBC reports that the ruling coalition has split over reinstatement of the judges. The smaller PML-N party, led by Nawaz Sharif, is leaving the government. Sharif has demanded that the judges be fully reinstated with all their old powers. The larger PPP party, led by Asif Zardari, says that it is happy to reinstate the judges, but wants their powers limited.

Just before Musharraf sacked the judges, they were due to rule on two issues. One was the constitutionality of Musharraf's election, but the other was an amnesty that the general had given to Zardari. Zardari has long had a reputation for shadiness, and it hard to see his actions now as anything other than an attempt to prevent himself from facing another round of corruption charges. Sharif in the past has sometimes come across as a bit of a clown, but current events allow him to portray himself credibly as a man of lofty principles.

Just before Musharraf sacked the judges, they were due to rule on two issues. One was the constitutionality of Musharraf's election, but the other was an amnesty that the general had given to Zardari. Zardari has long had a reputation for shadiness, and it hard to see his actions now as anything other than an attempt to prevent himself from facing another round of corruption charges. Sharif in the past has sometimes come across as a bit of a clown, but current events allow him to portray himself credibly as a man of lofty principles.

10 May, 2008

Western Sahara, slight return

If you are interested in the usefulness or otherwise of Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic travel documents, check out my recent posting on Somaliland, in the comments for which a citizen of the SADR discusses just what you can do with a passport from his country.

08 May, 2008

LEBANON IN CRISIS!

I could have posted an article headed "Lebanon in Crisis!" at any point over the last two years, and it would have been the same crisis. The country has been locked into a political conflict between pro- and anti- Syrian factions. Syrian hegemony was a tacit condition of the peace deal that ended the Lebanese civil war, but one that some Lebanese politicians increasingly chafed against as the years went by. The assassination of Rafiq Hariri in 2005 crystalised opposition against Syria, and led to the emergence of government from which pro-Syrian parties have been excluded. These groups, and particularly the armed party Hezbollah, have objected to their exclusion from government, as another implicit feature of the deal that ended the war was that everyone would be in government all the time.

The current crisis has split Lebanon into two rival camps, but the cleavages are different to those of the civil war. In the 1970s, a collection of Maronite Christian militias squared off against a coalition of Muslim, Druze, and Palestinan groups. Now the Shia Muslim Hezbollah is in the pro-Syrian opposition, while the Druze party and various Sunni parties are in the anti-Syrian government. The Christians seem to be split. Christian politicians from the community's old political families are in the anti-Syrian camp, but the pro-Syrians have the charismatic former General Michel Aoun on their side.

Aoun's presence in the pro-Syrian camp is rather mysterious… in the early 1990s, he declared himself president of Lebanon and fought a quixotic war against the Syrians. His joining the pro-Syrian camp looks like naked political opportunism, but it is just possible that there is something else happening. The anti-Syrian government in Lebanon largely represents the elites who have dominated the country's politics for generations, while Hezbollah have a certain arriviste appeal and can credibly claim to be speaking for the long-marginalised Shia. My understanding is that Aoun, though a Maronite, is not from one of that community's old ruling families. He might therefore represent a revolt by Maronite have-nots against their betters.

Right now the situation seems very tense. The government are trying to shut down Hezbollah's private telecommunications network, something the party's leader views as a declaration of war. Roadblocks have sprung up across Beirut, and gun battles have broken out between Hezbollah fighters and people from Sunni parties. Lebanon's army commander, meanwhile, has warned that the army could disintegrate into its sectarian sub-units should the crisis continue.

So, is Lebanon at the beginning of a new civil war? It is hard to tell. In the rolling crisis since Hariri's murder, the country has seemed to be on the brink on a number of occasions. On each of these, however, the storm has not broken, even if the crisis has not been resolved. Perhaps on this occasion too, people will decide that they do not really have the stomach for a return to civil war, but it could also only be luck that has kept the country at relative peace for so long.

On a personal note, Lebanon is somewhere I spent a very pleasant holiday in 2002, and it is strange and depressing to see it descending into chaos. As with the Israel-Hezbollah war of 2006, it generates a cognitive dissonance to hear of people being killed in fighting on somewhere like Beirut's Corniche.

Links:

Five Killed in Beirut gun battles (BBC News article)

Robert Fisk: Lebanon descends into chaos as rival leaders order general strike (from The Independent)

Beirut Daily Star (Lebanon's English language newspaper)

Lebanese Political Journal (random English-language Lebanese blog; Irish readers should bear in mind that Beirut's Hamra Street is normally not unlike Dublin's Grafton Street)

The current crisis has split Lebanon into two rival camps, but the cleavages are different to those of the civil war. In the 1970s, a collection of Maronite Christian militias squared off against a coalition of Muslim, Druze, and Palestinan groups. Now the Shia Muslim Hezbollah is in the pro-Syrian opposition, while the Druze party and various Sunni parties are in the anti-Syrian government. The Christians seem to be split. Christian politicians from the community's old political families are in the anti-Syrian camp, but the pro-Syrians have the charismatic former General Michel Aoun on their side.

Aoun's presence in the pro-Syrian camp is rather mysterious… in the early 1990s, he declared himself president of Lebanon and fought a quixotic war against the Syrians. His joining the pro-Syrian camp looks like naked political opportunism, but it is just possible that there is something else happening. The anti-Syrian government in Lebanon largely represents the elites who have dominated the country's politics for generations, while Hezbollah have a certain arriviste appeal and can credibly claim to be speaking for the long-marginalised Shia. My understanding is that Aoun, though a Maronite, is not from one of that community's old ruling families. He might therefore represent a revolt by Maronite have-nots against their betters.

Right now the situation seems very tense. The government are trying to shut down Hezbollah's private telecommunications network, something the party's leader views as a declaration of war. Roadblocks have sprung up across Beirut, and gun battles have broken out between Hezbollah fighters and people from Sunni parties. Lebanon's army commander, meanwhile, has warned that the army could disintegrate into its sectarian sub-units should the crisis continue.

So, is Lebanon at the beginning of a new civil war? It is hard to tell. In the rolling crisis since Hariri's murder, the country has seemed to be on the brink on a number of occasions. On each of these, however, the storm has not broken, even if the crisis has not been resolved. Perhaps on this occasion too, people will decide that they do not really have the stomach for a return to civil war, but it could also only be luck that has kept the country at relative peace for so long.

On a personal note, Lebanon is somewhere I spent a very pleasant holiday in 2002, and it is strange and depressing to see it descending into chaos. As with the Israel-Hezbollah war of 2006, it generates a cognitive dissonance to hear of people being killed in fighting on somewhere like Beirut's Corniche.

Links:

Five Killed in Beirut gun battles (BBC News article)

Robert Fisk: Lebanon descends into chaos as rival leaders order general strike (from The Independent)

Beirut Daily Star (Lebanon's English language newspaper)

Lebanese Political Journal (random English-language Lebanese blog; Irish readers should bear in mind that Beirut's Hamra Street is normally not unlike Dublin's Grafton Street)

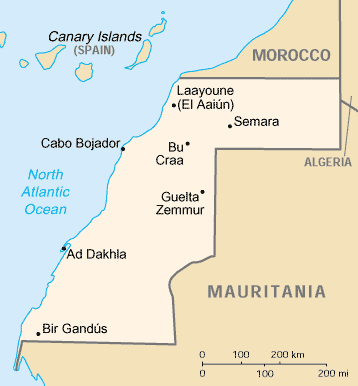

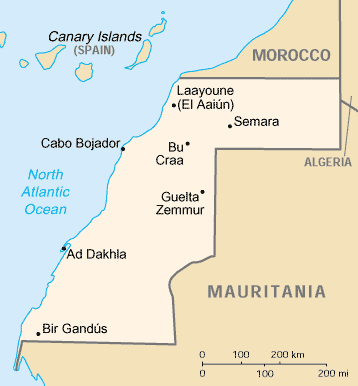

Phantom Countries: Western Sahara

And now we travel to a different kind of phantom country, one generally known as Western Sahara, though its official names is actually the Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic. My previous two phantoms, Taiwan and Somaliland, are examples of places that have many of the things one associates with independent states, but little or no recognition as such. Western  Sahara's situation is the opposite. There is very little territory controlled by a self-declared Western Sahara, but as a country it has quite a lot of recognition. Quite a few African and Third World countries maintain diplomatic relations with the SADR, and the idea that there ought to be a Western Sahara is one that retains a lot of support (or lip service) beyond those who formally recognise the SADR. If you look at a world atlas, there is a good chance that Western Sahara will be shown as an independent country, even if it does not exist in any real sense.

Sahara's situation is the opposite. There is very little territory controlled by a self-declared Western Sahara, but as a country it has quite a lot of recognition. Quite a few African and Third World countries maintain diplomatic relations with the SADR, and the idea that there ought to be a Western Sahara is one that retains a lot of support (or lip service) beyond those who formally recognise the SADR. If you look at a world atlas, there is a good chance that Western Sahara will be shown as an independent country, even if it does not exist in any real sense.

So what is this Western Sahara? In the colonial period, it was an Atlantic coast possession of Spain, gaining its rather unimaginative name from its being at the western end of the Sahara desert. As the wind of change blew through Africa, an independence movement emerged in the region, calling itself POLISARIO. In 1975, Spain withdrew from the territory, but by prior agreement it was immediately invaded by Mauritania and Morocco, who carved it up between them. POLISARIO launched a guerrilla war against both of them, with the support of Algeria. Their struggle had the implicit support of the International Court of Justice, which had ruled that the people of the territory were entitled to self-determination.

Initially, POLISARIO's war went well. Mauritania found the going particularly hard. A change of regime there led to Mauritania withdrawing from Western Sahara in 1979 and recognising the rights of the Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic that POLISARIO had declared in 1976. Morocco, however, simply extended its zone to include as much of the Mauritanian territory as it could. Militarily, the Moroccans were able to turn the tables on POLISARIO by fortifying the parts of the country that had the towns and mineral resources, leaving the rebels only with empty desert. At this point the war stalemated, and a ceasefire was agreed in 1991.

The 1991 ceasefire was meant to be the prelude to a settlement of the dispute, but instead it has frozen the conflict. 1992 was meant to see a referendum on whether the territory would join Morocco or become independent; this vote has never taken place, largely because of disputes over who would get to vote in it. The continuing stagnation favours the Moroccan regime, as it has been able to entrench its rule over the territory. It is very hard to see why it is worth POLISARIO's while engaging with this farcical non-peace process, yet if they return to arms, they will most likely be cast as the bad guys who are against peace. The Moroccan regime has also played the Western powers astutely – during the Cold War, they could not be pressured over the Western Sahara, for fear of strengthening the communists, and now it is vital that Morocco control the territory to prevent an al-Qaida take-over there (or in Morocco itself).

The 1991 ceasefire was meant to be the prelude to a settlement of the dispute, but instead it has frozen the conflict. 1992 was meant to see a referendum on whether the territory would join Morocco or become independent; this vote has never taken place, largely because of disputes over who would get to vote in it. The continuing stagnation favours the Moroccan regime, as it has been able to entrench its rule over the territory. It is very hard to see why it is worth POLISARIO's while engaging with this farcical non-peace process, yet if they return to arms, they will most likely be cast as the bad guys who are against peace. The Moroccan regime has also played the Western powers astutely – during the Cold War, they could not be pressured over the Western Sahara, for fear of strengthening the communists, and now it is vital that Morocco control the territory to prevent an al-Qaida take-over there (or in Morocco itself).

One possible glimmer of hope for the plucky Western Saharans was the outbreak in 2005 of disturbances within the Moroccan controlled areas of the territory. This "Independence Intifada" suggests a possible third course of action, between rolling over and accepting Moroccan rule or relaunching the war. At the same time, the balance of forces against Western Sahara is so strong that it is hard to see anything good happening there, unless major changes occur within Morocco itself.

Pictures from Wikipedia

Sahara's situation is the opposite. There is very little territory controlled by a self-declared Western Sahara, but as a country it has quite a lot of recognition. Quite a few African and Third World countries maintain diplomatic relations with the SADR, and the idea that there ought to be a Western Sahara is one that retains a lot of support (or lip service) beyond those who formally recognise the SADR. If you look at a world atlas, there is a good chance that Western Sahara will be shown as an independent country, even if it does not exist in any real sense.

Sahara's situation is the opposite. There is very little territory controlled by a self-declared Western Sahara, but as a country it has quite a lot of recognition. Quite a few African and Third World countries maintain diplomatic relations with the SADR, and the idea that there ought to be a Western Sahara is one that retains a lot of support (or lip service) beyond those who formally recognise the SADR. If you look at a world atlas, there is a good chance that Western Sahara will be shown as an independent country, even if it does not exist in any real sense.So what is this Western Sahara? In the colonial period, it was an Atlantic coast possession of Spain, gaining its rather unimaginative name from its being at the western end of the Sahara desert. As the wind of change blew through Africa, an independence movement emerged in the region, calling itself POLISARIO. In 1975, Spain withdrew from the territory, but by prior agreement it was immediately invaded by Mauritania and Morocco, who carved it up between them. POLISARIO launched a guerrilla war against both of them, with the support of Algeria. Their struggle had the implicit support of the International Court of Justice, which had ruled that the people of the territory were entitled to self-determination.

Initially, POLISARIO's war went well. Mauritania found the going particularly hard. A change of regime there led to Mauritania withdrawing from Western Sahara in 1979 and recognising the rights of the Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic that POLISARIO had declared in 1976. Morocco, however, simply extended its zone to include as much of the Mauritanian territory as it could. Militarily, the Moroccans were able to turn the tables on POLISARIO by fortifying the parts of the country that had the towns and mineral resources, leaving the rebels only with empty desert. At this point the war stalemated, and a ceasefire was agreed in 1991.

The 1991 ceasefire was meant to be the prelude to a settlement of the dispute, but instead it has frozen the conflict. 1992 was meant to see a referendum on whether the territory would join Morocco or become independent; this vote has never taken place, largely because of disputes over who would get to vote in it. The continuing stagnation favours the Moroccan regime, as it has been able to entrench its rule over the territory. It is very hard to see why it is worth POLISARIO's while engaging with this farcical non-peace process, yet if they return to arms, they will most likely be cast as the bad guys who are against peace. The Moroccan regime has also played the Western powers astutely – during the Cold War, they could not be pressured over the Western Sahara, for fear of strengthening the communists, and now it is vital that Morocco control the territory to prevent an al-Qaida take-over there (or in Morocco itself).

The 1991 ceasefire was meant to be the prelude to a settlement of the dispute, but instead it has frozen the conflict. 1992 was meant to see a referendum on whether the territory would join Morocco or become independent; this vote has never taken place, largely because of disputes over who would get to vote in it. The continuing stagnation favours the Moroccan regime, as it has been able to entrench its rule over the territory. It is very hard to see why it is worth POLISARIO's while engaging with this farcical non-peace process, yet if they return to arms, they will most likely be cast as the bad guys who are against peace. The Moroccan regime has also played the Western powers astutely – during the Cold War, they could not be pressured over the Western Sahara, for fear of strengthening the communists, and now it is vital that Morocco control the territory to prevent an al-Qaida take-over there (or in Morocco itself).One possible glimmer of hope for the plucky Western Saharans was the outbreak in 2005 of disturbances within the Moroccan controlled areas of the territory. This "Independence Intifada" suggests a possible third course of action, between rolling over and accepting Moroccan rule or relaunching the war. At the same time, the balance of forces against Western Sahara is so strong that it is hard to see anything good happening there, unless major changes occur within Morocco itself.

Pictures from Wikipedia

06 May, 2008

Continuing to Betray the Future

The BBC reports that the government of Turkmenistan has decided to move the golden statue of the late President Saparmurat Niyazov from the centre of the capital, Ashgabat. As you know, this was topped by golden statue of Nizayov that turned throughout the day so that it would always face the sun. The statue will now be located near a highway on the edge of the city. It is not known if it will continue to rotate.

The BBC reports that the government of Turkmenistan has decided to move the golden statue of the late President Saparmurat Niyazov from the centre of the capital, Ashgabat. As you know, this was topped by golden statue of Nizayov that turned throughout the day so that it would always face the sun. The statue will now be located near a highway on the edge of the city. It is not known if it will continue to rotate.The New York Times, meanwhile, reports that Nizayov-era bans on opera, ballet, and the circus have also been revoked: 'A Turkmen Dismantles Reminders of Old Ruler'

Picture from the BBC article.

Hat tip to my learned colleagues from ILX

04 May, 2008

2008: the year millions starve to death?

One thing I really need to write more about is the world food crisis. It is quite striking how this has exploded into the media over the last two months, and I expect it to become a bigger story as food prices continue to rise and increasing numbers of people across the world become unable to feed themselves and their families. I want to write more about this, not so much because any insights I have into the issue are likely to be that fascinating, but more because what I have written so far about it has been pretty facile. Biofuel is definitely not helping the situation, but it is rather simplistic to say that the turning over of relatively small tracts of land to ethanol production is the cause of recent steep rises in world food prices.

Pakistani Judges

The BBC has an interesting article on the recent reinstatement of senior judges in Pakistan: Saga of restoring Pakistani judges

As you know, when Pakistan's president, Pervez Musharraf, staged his autogolpe last year, he illegally sacked a load of senior judges, for fear that they might rule that his unconstitutional acts were unconstitutional. He replaced these judges with some lickspittle toady judges who could be relied upon to give convenient verdicts. Musharraf's autogolpe ultimately failed - although he remains in office as president, effective power now seems to lie with the coalition government of the Pakistan People's Party (PPP) and the Pakistan Muslim League Nawaz (PPP-N). This issue of reinstating the sacked judges has become a source of tension within the government. Nawaz Sharif, head of the PML-N, has taken a hard line, demanding that the sacked judges be reinstated and that the quisling judges who took their jobs be themselves sacked. The PPP (led by Asif Zardari, Benazir Bhutto's widower, and Prime Minister Yusuf Raza Gillani, meanwhile, has taken a more cautious line, arguing that the reinstatement of the judges should take place in the context of a general reform of the judiciary, and that the judges who took the sacked judges' jobs should merely revert to their former positions.

A compromise between the coalition partners seems to have been reached - the judges will be reinstated later this month, and the ones Musharraf promoted will take up their old jobs. However, there are still stormy waters ahead. The incumbent judges could try to keep their flash jobs by ruling against the reinstatement of their predecessors. There is also the theoretical possibility that Musharraf could invoke his constitutional powers to sack the government, in order to prevent the return of judges who might well rule that his continued holding of the presidency is unconstitutional; this is however unlikely, given his total lack of credibility and the government's recent electoral mandate.

One final exciting thing about all this is that the reinstatement of the judges could mean that everything that happened since they were sacked occurred in a legal void, with pretty much everything happening since Musharraf declared his state of emergency being up for legal challenge.

As you know, when Pakistan's president, Pervez Musharraf, staged his autogolpe last year, he illegally sacked a load of senior judges, for fear that they might rule that his unconstitutional acts were unconstitutional. He replaced these judges with some lickspittle toady judges who could be relied upon to give convenient verdicts. Musharraf's autogolpe ultimately failed - although he remains in office as president, effective power now seems to lie with the coalition government of the Pakistan People's Party (PPP) and the Pakistan Muslim League Nawaz (PPP-N). This issue of reinstating the sacked judges has become a source of tension within the government. Nawaz Sharif, head of the PML-N, has taken a hard line, demanding that the sacked judges be reinstated and that the quisling judges who took their jobs be themselves sacked. The PPP (led by Asif Zardari, Benazir Bhutto's widower, and Prime Minister Yusuf Raza Gillani, meanwhile, has taken a more cautious line, arguing that the reinstatement of the judges should take place in the context of a general reform of the judiciary, and that the judges who took the sacked judges' jobs should merely revert to their former positions.

A compromise between the coalition partners seems to have been reached - the judges will be reinstated later this month, and the ones Musharraf promoted will take up their old jobs. However, there are still stormy waters ahead. The incumbent judges could try to keep their flash jobs by ruling against the reinstatement of their predecessors. There is also the theoretical possibility that Musharraf could invoke his constitutional powers to sack the government, in order to prevent the return of judges who might well rule that his continued holding of the presidency is unconstitutional; this is however unlikely, given his total lack of credibility and the government's recent electoral mandate.

One final exciting thing about all this is that the reinstatement of the judges could mean that everything that happened since they were sacked occurred in a legal void, with pretty much everything happening since Musharraf declared his state of emergency being up for legal challenge.

03 May, 2008

Betraying the Future

President Saparmurat Niyazov of Turkmenistan renamed the months of the year after members of his family (and other historical figures). January became Turkmenbashi (Father of the Turkmen), after a title he awarded himself.

Niyazov died in 2006. His successor, President Kurbanguly Berdymukhamedov, has just ordered the months to revert to their former names. It is not clear if there are any plans to remove or alter any of the country's golden statues to Niyazov.

Niyazov died in 2006. His successor, President Kurbanguly Berdymukhamedov, has just ordered the months to revert to their former names. It is not clear if there are any plans to remove or alter any of the country's golden statues to Niyazov.

01 May, 2008

Cameroon Diary

One of my former classmates is now in the town of Maga in Cameroon. He is working with the authorities there on a development plan for the locality. And he has a blog about what he is doing there: Tom in Africa

Phantom Countries: Somaliland

And so to Somaliland. This is a northern part of Somalia, and its attempt to achieve statehood is an example of see-you-around-suckers secession. As you know, the Somali state largely collapsed during the 1990s, with country's territory being taken over by feuding warlords and suchlike. The northern part of the country, however, managed to escape the general chaos that swept the rest of the country. The locals there managed to setup a separate administration and state-like apparatus, albeit one facing a lot of challenges. The leaders of this northern region then proposed to escape permanently from the rest of Somalia's ongoing nightmare by declaring their area independent, and naming it Somaliland.

Thus far no one has granted Somaliland formal recognition. This is not particularly surprising. The international community abhors secession. In Africa, in particular, there is a far that should any borders start to be re-drawn then the whole continent could slip into the abyss as ambitious leaders try to carve out little empires for themselves. But Somaliland has one ace up its sleeve that means it continuously hovers on the brink of formal acceptance in the family of nations. Its borders are the same as those of the pre-independence colony of British Somaliand. This was merged into Italian Somaliland to create the state we know and love as Somalia, but the Somaliland leaders can say that they are merely reversing this artificial union and bringing a previously existing entity back into being as an independent state. The Somalilanders are invoking the principle of uti possidetis, that post-colonial borders should by default follow pre-independence boundaries. This is good (for them), as it allows the prospect of their independence being recognised without setting a precedent that could lead to the disintegration of other countries.

abhors secession. In Africa, in particular, there is a far that should any borders start to be re-drawn then the whole continent could slip into the abyss as ambitious leaders try to carve out little empires for themselves. But Somaliland has one ace up its sleeve that means it continuously hovers on the brink of formal acceptance in the family of nations. Its borders are the same as those of the pre-independence colony of British Somaliand. This was merged into Italian Somaliland to create the state we know and love as Somalia, but the Somaliland leaders can say that they are merely reversing this artificial union and bringing a previously existing entity back into being as an independent state. The Somalilanders are invoking the principle of uti possidetis, that post-colonial borders should by default follow pre-independence boundaries. This is good (for them), as it allows the prospect of their independence being recognised without setting a precedent that could lead to the disintegration of other countries.

That's about it for Somaliland. Various reports and stuff have recommended that it be allowed to join the family of nations, but for the moment the country remains unrecognised. If the rest of Somalia were to start showing signs of stabilisation then I imagine that the Somalilanders would be pressured to re-integrate with their former compatriots. But there is no prospect of that happening any time soon. The expectation has to be that Somaliland will sooner or later gain external recognition. In the meantime, this phantom country chugs along. Apparently it is quite nice to visit; its unrecognised status does not prevent a trickle of tourists visiting from Djibouti and Ethiopia to sample the hospitality of this strangely peaceful land.

Would you like to know more? Oh look, the International Crisis Group has a two year old report on Somaliland: Somaliland: Time for African Union Leadership

Somaliland flag from Wikipedia

Thus far no one has granted Somaliland formal recognition. This is not particularly surprising. The international community

abhors secession. In Africa, in particular, there is a far that should any borders start to be re-drawn then the whole continent could slip into the abyss as ambitious leaders try to carve out little empires for themselves. But Somaliland has one ace up its sleeve that means it continuously hovers on the brink of formal acceptance in the family of nations. Its borders are the same as those of the pre-independence colony of British Somaliand. This was merged into Italian Somaliland to create the state we know and love as Somalia, but the Somaliland leaders can say that they are merely reversing this artificial union and bringing a previously existing entity back into being as an independent state. The Somalilanders are invoking the principle of uti possidetis, that post-colonial borders should by default follow pre-independence boundaries. This is good (for them), as it allows the prospect of their independence being recognised without setting a precedent that could lead to the disintegration of other countries.

abhors secession. In Africa, in particular, there is a far that should any borders start to be re-drawn then the whole continent could slip into the abyss as ambitious leaders try to carve out little empires for themselves. But Somaliland has one ace up its sleeve that means it continuously hovers on the brink of formal acceptance in the family of nations. Its borders are the same as those of the pre-independence colony of British Somaliand. This was merged into Italian Somaliland to create the state we know and love as Somalia, but the Somaliland leaders can say that they are merely reversing this artificial union and bringing a previously existing entity back into being as an independent state. The Somalilanders are invoking the principle of uti possidetis, that post-colonial borders should by default follow pre-independence boundaries. This is good (for them), as it allows the prospect of their independence being recognised without setting a precedent that could lead to the disintegration of other countries.That's about it for Somaliland. Various reports and stuff have recommended that it be allowed to join the family of nations, but for the moment the country remains unrecognised. If the rest of Somalia were to start showing signs of stabilisation then I imagine that the Somalilanders would be pressured to re-integrate with their former compatriots. But there is no prospect of that happening any time soon. The expectation has to be that Somaliland will sooner or later gain external recognition. In the meantime, this phantom country chugs along. Apparently it is quite nice to visit; its unrecognised status does not prevent a trickle of tourists visiting from Djibouti and Ethiopia to sample the hospitality of this strangely peaceful land.

Would you like to know more? Oh look, the International Crisis Group has a two year old report on Somaliland: Somaliland: Time for African Union Leadership

Somaliland flag from Wikipedia

The Lisbon Treaty and Irish Euroscepticism

I was out for dinner with some of my former spymates last Saturday. One of the people there is involved in a campaign against the Lisbon Treaty, and was talking about it with the rest of us. By her own admission, she was rather boring us. At the time I though, well, the Lisbon Treaty is boring, what do you expect? In retrospect, though, it struck me that if a group of former and current International Relations students are not interested in discussing the Lisbon Treaty, then who is?

From that, let me segue into a link to an article appearing on the website of the Dublin Review of Books: 'Battling the Beast of Brussels', by Tony Brown, brought to my attention in a blog post by Nicholas Whyte. Tony Brown is involved with the Institute of European Affairs, a think-tank that promotes the cause of European integration.

Even if you are not that engaged with the Lisbon Treaty, you may be aware that Ireland will shortly be having a referendum on it. Brown's article looks at the people who are campaigning in Ireland for a vote against the treaty. He points out that they are largely the same people and institutions that have campaigned against every previous EU treaty, and that on Lisbon they are making the same outlandish claims that they made in every previous case – that the treaty will lead to the creation of an EU super-army, or that it will lead to enforced abortions, or to the end of neutrality, or to everything being privatised, or to mass impoverishment, and so on. That this did not happen last time seems not to cause any embarrassment to those who said they would, nor does it prevent them being predicted again the next time an EU treaty comes up for ratification.

From that, let me segue into a link to an article appearing on the website of the Dublin Review of Books: 'Battling the Beast of Brussels', by Tony Brown, brought to my attention in a blog post by Nicholas Whyte. Tony Brown is involved with the Institute of European Affairs, a think-tank that promotes the cause of European integration.

Even if you are not that engaged with the Lisbon Treaty, you may be aware that Ireland will shortly be having a referendum on it. Brown's article looks at the people who are campaigning in Ireland for a vote against the treaty. He points out that they are largely the same people and institutions that have campaigned against every previous EU treaty, and that on Lisbon they are making the same outlandish claims that they made in every previous case – that the treaty will lead to the creation of an EU super-army, or that it will lead to enforced abortions, or to the end of neutrality, or to everything being privatised, or to mass impoverishment, and so on. That this did not happen last time seems not to cause any embarrassment to those who said they would, nor does it prevent them being predicted again the next time an EU treaty comes up for ratification.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)