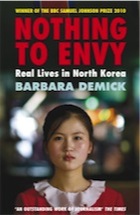

This is a book about North Korea by an American journalist. She attempts to sketch everyday life in that most isolated country by talking to a number of people who have defected to South Korea from it. Mindful of the problems associated with exile narratives (almost by definition, exiles are going to be disaffected from the country they have left and may also be inclined to tell a listener the story they want to hear), Demick bases her book on a small number of exiles from the city of Chongjin in the north east of the country. The logic of this is that picking people from the same place means that she can cross-reference incidental details about the town in their narratives as a way of gauging their overall truthfulness. That's what she tells us in the introduction anyway. In the book as a whole she presents the defectors' narratives as Fact, without ever questioning whether they might be presenting a self-serving narrative. Perhaps she weeded out other subjects who she felt were feeding her bullshit, though she does not mention this.

This is a book about North Korea by an American journalist. She attempts to sketch everyday life in that most isolated country by talking to a number of people who have defected to South Korea from it. Mindful of the problems associated with exile narratives (almost by definition, exiles are going to be disaffected from the country they have left and may also be inclined to tell a listener the story they want to hear), Demick bases her book on a small number of exiles from the city of Chongjin in the north east of the country. The logic of this is that picking people from the same place means that she can cross-reference incidental details about the town in their narratives as a way of gauging their overall truthfulness. That's what she tells us in the introduction anyway. In the book as a whole she presents the defectors' narratives as Fact, without ever questioning whether they might be presenting a self-serving narrative. Perhaps she weeded out other subjects who she felt were feeding her bullshit, though she does not mention this.The book follows its characters from roughly the late 1980s to their escapes to South Korea in the early 21st century, with an epilogue on their adjustment to a new life in a very different country. The subjects represent something of a cross-section of society – a textile worker who is an ardent supporter of the regime, a high-flying science student, a school teacher, a paediatrician, and a young lad orphaned by the collapse of North Korean society.

This is basically a book about social collapse*. North Korea's economy tanked in the 1990s. Previously the country had been relatively wealthy in world historical terms, with North Koreans even enjoying a higher standard of living than their southern neighbours until the South began to take off in the 1960s. However, the North Korean economy was dependent on imports of oil and other commodities from the Soviet Union, supplied at well below world prices. When the USSR went into decline in the later 1980s and then broke up in the 1990s, North Korea found itself unable to pay for oil now being priced at market rates. North Korean industry collapsed, as did agricultural output, which was dependent on oil-derived fertilisers and farm machinery that could no longer be powered. That the government of what is perhaps the world's most militarised country insisted on ploughing so much of its resources into the armed forces probably did not help much either. North Korea fell into a famine in which it is estimated that a tenth of the population died.

Focussing on individual stories gives us an idea of the human scale of this catastrophe. Mrs Song, the textile worker, is sent home from her job as no raw materials are coming in. She then has to set aside her socialist principles to become a black market trader, but it is still not enough to stop her husband, son, and mother-in-law dying of starvation. Even more harrowing are the stories of the paediatrician and school teacher, who have to watch their charges starve to death.

For all the grimness of a land stalked by famine, the most affecting story in the book is that of Mi-Ran and Jun-Sang, the school teacher and the high-flying student. They loved each other, but in North Korea their love was doomed. Jun-Sang's academic excellence meant that he was upwardly mobile, but Mi-Ran had a tainted family background – her father was a South Korean who had been captured in the Korean War and settled in the North. If Jung-San's association with Mi-Ran had become public knowledge then her taint would doom his dreams of advancement. Mi-Ran eventually realises that their relationship could go no further, and skips out of North Korea, eventually ending up in Seoul. Jun-Sang eventually makes the same journey, but when they meet again it is too late for them, as Mi-Ran now had a child and husband. More than all the death, this blight cast on everyday lives brought home to me the nastiness of the North Korean regime.

Anyway, I recommend this book highly. It humanises the people of one of the world's strangest countries and gives an insight into a world of strangeness that most of us will never live through. Still, reading it has made me think a bit more about the precarious nature of advanced human society. North Korea's economy collapsed when they lost their supply of cheap energy. What happens to us when we can no longer get the oil and gas we need at prices we can afford?

image source

*which means that it dovetails nicely with some of the fiction I have been reading recently about future social collapse: Stephen Baxter's Flood and Ark

No comments:

Post a Comment