Some time ago I said that I would take you all on a journey through the world of

International Relations theory. Sadly, the train had barely left the station when it faced a long delay in its

second stop, but now let’s get things moving again. And look, we are pulling in at the third stop, which is called Marxism. This is the third of International Relations’ big three theories, though it is very much the poor relation of Liberalism and Realism.

In broad outline you probably know what Marxism is all about. In some ways it is reducible to a string of buzzwords - class struggle, dialectics, historical materialism, modes of production, relations of production, alienation, base & superstructure, surplus value, and so on. The interesting question is how applicable all this is to world politics. In his own writings, Karl Marx largely confined himself to analysing power structures within countries, saying very little about how the workings of capitalism work internationally.

Still, Marx says more than nothing about the world as a whole - there is a fascinating passage in

The Communist Manifesto of 1848 where he talk presciently of globalisation, and of capitalism’s insatiable urge to spread itself throughout the world, transforming all traditional societies it touches through the introduction of the cash nexus and capitalist relations of production. Nevertheless, the argument is somewhat unsophisticated in the light of later developments - capitalism is seen as turning the whole world into a simulacrum of the advanced industrial societies. The division of the world into a developed core and a (seemingly) permanently underdeveloped periphery does not look like something he envisaged.

After Marx’s death, others tried to develop his ideas and more complex Marxist ideas of relevance to International Relations

began to develop. V.I. Lenin, in works such as

Imperialism - The Highest Stage of Capitalism, talked about how through colonialism and overseas investment capitalism had become transnational, that in a sense entire countries had become bourgeois or proletarian. Lenin’s grasp of economics was much weaker than Marx’s, and his belief that colonialism was driving the world into world war seems a bit simplistic when you look at how the First World War actually started. Nevertheless, Lenin was in retrospect correct in identifying Russia as capitalism’s weakest link, in so far as it was both an imperial state and (through extensive inward investment) a de facto colony, thus making it the place where world revolution was most likely to begin.

Lenin’s legacy for Marxism was ultimately malign - by achieving his revolution and identifying Marxism (or Marxism-Leninism) as the state ideology, Marxism was tied to the USSR’s fortunes and forced through conceptual hoops to support whatever twist in policy the country’s leadership felt like espousing. The USSR’s quarter century rule by a psychopath also did not help. That end of Marxism gradually lost any intellectual credibility, and I doubt anyone in the world now seriously reads Marxist scholarship originating in the USSR.

In the west, however, a separate Marxist tradition developed in academia, divorced from the rough and tumble of actual politics. Marx himself would probably have been appalled by this development, given that he devoted as much effort to organising socialist movements as he did to research and writing, but the ivory tower academics have kept his ideas alive. Unfortunately for the International Relations student, the ideas of these intellectual Marxists have gone in many different directions. Some of these roads have produced lines of thought relevant to our discipline, such as Dependency Theory or various strands of Critical Theory. However, these have either evolved so far from original Marxist orthodoxy as to be essentially post-Marxist, or they have been almost completely discredited by the passage of time (or both). I would therefore question whether one could still talk of a "pure" Marxism as having any great relevance to International Relations.

Nevertheless, Marxism has one major contribution to our subject. When you look at writings in the Realist or Liberal tradition, the focus is all on diplomacy, states, armies, treaties, statesmen, and high politics. When you look at what Marxist writers talk about, you see stuff about economics, companies, exploitation, class, and so on. In some ways that makes Marxism look like it is from a completely different discipline to "true" International Relations. However, the question can be turned on its head by asking whether it is actually the old-school theories that are missing the point and ignoring what is actually relevant to the way the world works. Marxism is also important in that it explodes the idea that states are unitary actors working for the good of all their citizens - rather we see conflict within states which in turn is bound to affect how they operate internationally.

In the end, Marxism is probably more relevant to International Relations because of the questions it asks rather than the answers it provides. Others have taken those questions and answered them in ways that go beyond anything Marx would have envisaged.

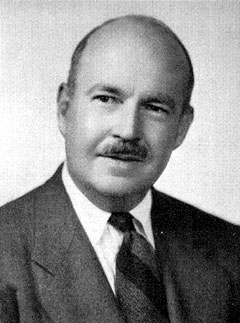

I have been thinking for a while about maybe doing a thesis on the relationship between the president and prime minister of the Palestinian Authority, going back to the period when Abbas was appointed as prime minister to Arafat's president. I could do some kind of comparative analysis based on the literature on other semi-presidential polities and make observations on how the office-holders have or have not managed to leverage the power of their offices.

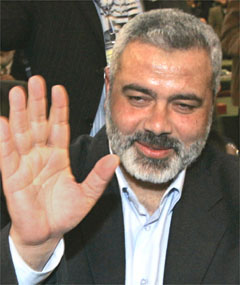

I have been thinking for a while about maybe doing a thesis on the relationship between the president and prime minister of the Palestinian Authority, going back to the period when Abbas was appointed as prime minister to Arafat's president. I could do some kind of comparative analysis based on the literature on other semi-presidential polities and make observations on how the office-holders have or have not managed to leverage the power of their offices.  (as you know, the Palestinian prime minister is from Hamas and the president from Fatah). Last week there was the ghoulish episode of a prominent Fatah leader's children being murdered by gunmen outside their school. On Thursday, there seems to have been an attempt on the life of Ismail Haniyeh, the prime minister, with Haniyeh publicly accusing the senior Fatah figure Mohammed Dahlan of ordering the attack. Today President Mahmoud Abbas has called for joint elections to the parliament and presidency to resolve the political deadlock. Presumably he is assuming that in simultanaeous election the same side will win both elections, and hoping that he has the prestige to win these elections.

(as you know, the Palestinian prime minister is from Hamas and the president from Fatah). Last week there was the ghoulish episode of a prominent Fatah leader's children being murdered by gunmen outside their school. On Thursday, there seems to have been an attempt on the life of Ismail Haniyeh, the prime minister, with Haniyeh publicly accusing the senior Fatah figure Mohammed Dahlan of ordering the attack. Today President Mahmoud Abbas has called for joint elections to the parliament and presidency to resolve the political deadlock. Presumably he is assuming that in simultanaeous election the same side will win both elections, and hoping that he has the prestige to win these elections.