As you know, Hamas (an Islamist political-military movement) currently exercise day-to-day control of the Gaza Strip region of Palestine (while the Israelis control its borders and airspace). From there, Hamas and other groups have been firing Qassam rockets across into Israeli border towns. As well as killing people and damaging property, this is causing great annoyance in Israel. Israeli forces have staged incursions and bombing raids into Gaza, killing many more people and destroying much more property than the rocket attacks; they have also run a blockade of the Gaza Strip, reducing the amount of foodstuffs and so on available to people there. The Israelis have, however, been unsuccessful at preventing the rockets from flying across the border.

Recently there has been some talk from Hamas of instituting either a hudna (truce) or a taddhiyya (period of calm, in which military operations would be downscaled) with the Israeli state. This would not be unprecedented, as Hamas has operated several such hudnas and taddhiyyas in the past. There was a slightly so-what quality to them in the longer term, as they failed to achieve any breakthrough in the political morass of Palestine-Israel; crucially, the Israeli state continued to assassinate Hamas activists and carry out offensive operations, and Hamas ceasefires would typically breakdown after the killing of a Hamas leader or the butchering of some Palestinian civilians who happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. From the Israeli side, the Hamas ceasefires seemed rather inconsequential, given that they did not cover other militant groups such as Islamic Jihad. Nor were they always strictly observed by Hamas cadres.

The current situation seems a bit different. The talk from Hamas of a ceasefire in Gaza was initially scoffed at by the Israeli establishment and taken as a sign that the movement was hurting as a result of Israeli military action. Then some government ministers broke ranks. Perhaps registering that military action was neither halting the Qassams nor securing the release of kidnapped Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit, some Israeli government ministers have suggested that a serious truce offer from Hamas should not be rejected. While these people are still placing hoops for Hamas to jump through, they are talking about concrete issues rather than the symbolic demands on which the Israeli state is traditionally fixated. It is perhaps also significant that the politicians talking about engagement with Hamas are from the mainstream of Israeli politics and not its pacifist fringes; Shaul Mofaz is from the Kadima party of Ariel Sharon and current prime minister Ehud Olmert, while Binyamin Ben-Eliezer is from the hard-nut end of Labour.

For the moment, all this talk about truces and engagement with Hamas is just talk. Israel's prime minister, Ehud Olmert, has rejected any kind of engagement with Hamas unless the movement formally recognises Israel, something the movement is unlikely to ever do. The military campaign against Hamas will continue indefinitely, whether Hamas declares a truce or not. Perhaps not entirely coincidentally, another Israeli government minister announced the expansion of Israeli settlements in Palestinian East Jerusalem. So maybe we are in for more of the same next year, or maybe the public position of Mofaz and Ben-Eliezer suggests that there are subterranaean movemens taking place within the Israeli body politic.

23 December, 2007

05 December, 2007

The Postmodern White House

You may recall that I was discussing theoretical approaches to International Relations. That ran into the ground a bit, sadly before I reached any of the more entertaining theories. One day I will climb back on the wagon.

You may recall that I was discussing theoretical approaches to International Relations. That ran into the ground a bit, sadly before I reached any of the more entertaining theories. One day I will climb back on the wagon.In the meantime, an entertaining thing to do can be to look at real world political leaders or organisations, and try to work out what is their theoretical perspective. Take George W. Bush (please, take him*). Like most people, he probably does not think of himself as having a theoretical perspective, he just does things he reckons will advance whatever goals he happens to have at hand. Or maybe he just does things (the whole idea of people actually having clearly defined goals that they rationally work to advance is surprisingly problematic when applied to real situations). However, one can still look at what he says and does and attempt to deduce the perspectives that guide him, even if they are subconscious.

The Bush regime is sometimes seen as embodying a realist view of international relations, with all that willingness to project US power wherever they like and tell anyone who doesn't like it to shag off. But the current US administration is also often seen as being driven by liberalism, albeit a kind of crusading bad-ass liberalism far removed from the stereotypes of hand-wringing whingey liberalism. From this point of view, it is Bush's liberalism that drove him to invade loads of countries and threaten bloody war on others - he is trying to make the world a better place, and you can't make an omelette without breaking eggs.

It might be, though, that in trying to place the White House in terms of the old-school big two of International Relations theory, people are missing the point big time. We live now in the 21st century, and the Enlightenment derived certainties that drove people in the past are looking distinctly frayed around the ages. Realism and liberalism are both approaches from within the tired Enlightenment tradition... could it be that in our post-Enlightenment era, the current US administration is driven by post-modern ideas?

It might be, though, that in trying to place the White House in terms of the old-school big two of International Relations theory, people are missing the point big time. We live now in the 21st century, and the Enlightenment derived certainties that drove people in the past are looking distinctly frayed around the ages. Realism and liberalism are both approaches from within the tired Enlightenment tradition... could it be that in our post-Enlightenment era, the current US administration is driven by post-modern ideas?In 2002, some journalist fellow called Ron Suskind talked with a Senior White House Figure. The SWHF took issue with something the journalist had written, and berated him for belonging to a "reality-based community", defined as being people who "believe that solutions emerge from your judicious study of discernible reality". The SWHF went on talk about how the world no longer conforms to this paradigm: ''We're an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality" (SWHF quotes from this article by Ron Suskind: Faith, Certainty and the Presidency of George W. Bush)

A key feature of the postmodern worldview is to repudiate the idea of objective reality. Instead, people construct a reality for themselves. Ideas and theories become more important than mere facts, and if you can get enough people to believe something you have created your own reality. Suskind's contact suggests that at least some people in the White House buy in to this kind of postmodern perspective.

The last few days have seen another example of the Bush regime's postmodern view of reality. Over the last while, the Bush administration has been talking a lot about how Iran has a nuclear weapons programme and how something needs to be done about it; that "something" is implicitly war of one sort or another. However, US intelligence officials have released a report that says that there is strong evidence to support the idea that the Iranian regime halted its nuclear weapons programme in 2003. While one could argue that this evidence supports the idea that a tough Western policy forced the Iranians away from nuclear weapons, it severely undermines the idea that Iran needs to be invaded or fucked up to stop it acquiring nuclear weapons in the very near future. President Bush, however, is determined to press ahead with his policy of ramping up sanctions against the Iranian regime, possibly as a way of building tensions that will have the way towards a US strike. Bush's response to the inconvenient, reality-based report of his intelligence community has been to ignore it - instead he has rhetorically urged Iran to come clean about its non-existent nuclear weapons programme. In doing so, he is attempting to conjure such a programme into being, at least in so far as it can be used as pretext for war.

The last few days have seen another example of the Bush regime's postmodern view of reality. Over the last while, the Bush administration has been talking a lot about how Iran has a nuclear weapons programme and how something needs to be done about it; that "something" is implicitly war of one sort or another. However, US intelligence officials have released a report that says that there is strong evidence to support the idea that the Iranian regime halted its nuclear weapons programme in 2003. While one could argue that this evidence supports the idea that a tough Western policy forced the Iranians away from nuclear weapons, it severely undermines the idea that Iran needs to be invaded or fucked up to stop it acquiring nuclear weapons in the very near future. President Bush, however, is determined to press ahead with his policy of ramping up sanctions against the Iranian regime, possibly as a way of building tensions that will have the way towards a US strike. Bush's response to the inconvenient, reality-based report of his intelligence community has been to ignore it - instead he has rhetorically urged Iran to come clean about its non-existent nuclear weapons programme. In doing so, he is attempting to conjure such a programme into being, at least in so far as it can be used as pretext for war.Pictures from, in order: Wikipedia, Wikipedia, and the BBC.

* Thank you, I am here all week

02 December, 2007

The Collateral Damage of Colonialism

Here is an interesting blog post on the possible development of HIV/AIDS in the years before the 1980s: Notes towards a pre-1981 history of HIV/AIDS. Randy McDonald, the post's author, suggests that it was the social dislocation wrought be colonialism (and in particular the exploitation by France and Belgium of rubber resources in the Congo basin) that led to the virus crossing from animals and then being able to spread through the human population.

29 November, 2007

More Lolcrime

And again, not so funny if you are the person on trial.

In Iran, Mehrnoushe Solouki, a French-Iranian national resident in Canada, is in custody awaiting trial. She is a documentary film-maker, and is accused not of actually doing anything, but of intending to make a film critical of the Iranian regime (it was thought that she might be intending to include footage of mass graves of people massacared by the regime in 1988. She has received one piece of good news while in jail awaiting trial - the prison authorities have said that they probably will not torture her to death, like in 2003 they did Zahra Kazemi, a Canadian-Iranian journalist. Thanks to Randy McDonald for alerting me to this disturbing story.

Meanwhile, in Sudan, Gillian Gibbons has been jailed for letting her pupils vote to name a teddy bear Mohammed. She was apparently lucky to escape receiving 40 lashes. The people who run Sudan are pretty funny guys - I remember reading some years ago that they were planning to deploy Jinn against the rebels in the country's south (I really wish I had a source for this, other than "I read it somewhere").

In Iran, Mehrnoushe Solouki, a French-Iranian national resident in Canada, is in custody awaiting trial. She is a documentary film-maker, and is accused not of actually doing anything, but of intending to make a film critical of the Iranian regime (it was thought that she might be intending to include footage of mass graves of people massacared by the regime in 1988. She has received one piece of good news while in jail awaiting trial - the prison authorities have said that they probably will not torture her to death, like in 2003 they did Zahra Kazemi, a Canadian-Iranian journalist. Thanks to Randy McDonald for alerting me to this disturbing story.

Meanwhile, in Sudan, Gillian Gibbons has been jailed for letting her pupils vote to name a teddy bear Mohammed. She was apparently lucky to escape receiving 40 lashes. The people who run Sudan are pretty funny guys - I remember reading some years ago that they were planning to deploy Jinn against the rebels in the country's south (I really wish I had a source for this, other than "I read it somewhere").

24 November, 2007

Infrastructure Diplomacy

I was talking to a guy at a conference yesterday. He was telling me that the EU is slashing the amount of money it spends on health and education in Africa; instead, the money is going to be focussed on infrastructure projects. There might be sound reasoning behind this, with some sort of calculations leading to the conclusion that spending on infrastructure is a more effective way of moving African countries towards sustainable development and self-reliance. However, it is widely believed that the real reason for the change in spending priorities is political. China has over the last couple of years earned itself a lot of kudos with African regimes by building roads and bridges for them. The EU now feels the need to compete – it is important that when an African looks at a bridge, they know it was built by the EU and not by China.

20 November, 2007

Russians Can't Get Enough of Vladimir Putin

The BBC reports that a petition calling for Vladimir Putin to remain "national leader" has been signed by 30 million Russians; this is more than a fifth of the country's total population. The constitution currently prevents Putin from seeking re-election when his current presidential term expires next March. However, Vladimir Voronin of the For Putin group points out that constitutions can be changed, as only God's law is immutable. Putin has always said that he would not seek re-election, but as previously noted, there is nothing to prevent him becoming the country's prime minister and transforming that office into the country's main leadership position.

The BBC reports that a petition calling for Vladimir Putin to remain "national leader" has been signed by 30 million Russians; this is more than a fifth of the country's total population. The constitution currently prevents Putin from seeking re-election when his current presidential term expires next March. However, Vladimir Voronin of the For Putin group points out that constitutions can be changed, as only God's law is immutable. Putin has always said that he would not seek re-election, but as previously noted, there is nothing to prevent him becoming the country's prime minister and transforming that office into the country's main leadership position.

19 November, 2007

11 November, 2007

Pakistan: Lolcountry

Just over a week ago, Pervez Musharraf decided to once more tear up Pakistan's consitution. Even before that I had been pondering why Pakistan is such an unsuccessful country, largely triggered by discussions of its progress since independence in articles commenting on it being 50 years since the British left it and India. India, on the other hand, seems to have done pretty well, at least when compared to Pakistan. OK, so India does have its problems (grinding poverty and communal tensions spring to mind), but Pakistan has these problems and a load of crazy other ones as well. I am thinking of things like Pakistan's inability to embed democratic rule, and its having an army that sees itself as having a divine right to intervene politically whenever it feels like it. Or the country's venal and shortsighted political elite. Or the country's secret service (the ISI), who seem to run their own separate foreign policy only tangentially related to the official policies of the state's notional leaders. Or the state's general inability to see its writ run through large tracts of the country.

And so on. Pakistan seems particularly unsuccessful in the world of high international politics, managing to get stuffed out of it in at least two wars with its larger neighbour. One might, of course, see these outcomes as being largely inevitable, given the balance of resources between the two countries, but the Pakistani military went into both of these struggles expecting to triumph. Failure in the second of these saw Pakistan lose more than half of its population to Bangladesh.

In contrast, India has actual achievements to point to since it became independent. It has managed to run itself constitutionally, with its army never intruding itself into politics in the manner of Pakistan's generals. In recent years it has even become a major force in the world economy, and I think it has managed to make progress in the area of poverty reduction. The state as an institution suffers from a lot of the problems that afflict states elsewhere, but it does not seem from this distance to be so completely chaotic as that of Pakistan.

So, why has India succeeded, albeit modestly, while Pakistan has failed? The two countries would have had similar starting conditions, being both large heavily populated multi-ethnic societies. Perhaps the organising principles of the two countries are significant, with India being set up as a secular country containing people of various religions and cultural backgrounds, while Pakistan was intended as a Muslim state (or a state for Muslims). One could argue that shared religion is actually a weak glue with which to hold a society together, contrary to what the likes of Samuel Huntington would say. Or maybe there are other material factors of which I am unaware.

On current events in particular… before Musharraf's latest autogolpe, there was an interesting article in the London Review of Books on Pakistan by Tariq Ali ("Pakistan at Sixty"). Ali is the kind of leftist writer whose work you have to be careful with, but I was very struck by some of the points he made. Over the last year, the Pakistani regime has had some face-offs with Jihadi Islamists, and also with members of the legal profession, following an earlier attempt to remove the Chief Justice from office. Contrary to what you might assume, however, it was the attempt to crack down on judicial freedom that excited the most public reaction in Pakistan, with the legal profession spearheading mass demonstrations in many Pakistani cities. The lawyers have been at the forefront of attempts to stop Musharraf's latest plot, with Pakistan's lazy politicians largely following in the rear but nevertheless finding themselves swept into the strugge by public outrage. This is perhaps a hopeful sign, in a country where lawyers have previously been only too happy to roll over whenever it suited their military rulers.

And so on. Pakistan seems particularly unsuccessful in the world of high international politics, managing to get stuffed out of it in at least two wars with its larger neighbour. One might, of course, see these outcomes as being largely inevitable, given the balance of resources between the two countries, but the Pakistani military went into both of these struggles expecting to triumph. Failure in the second of these saw Pakistan lose more than half of its population to Bangladesh.

In contrast, India has actual achievements to point to since it became independent. It has managed to run itself constitutionally, with its army never intruding itself into politics in the manner of Pakistan's generals. In recent years it has even become a major force in the world economy, and I think it has managed to make progress in the area of poverty reduction. The state as an institution suffers from a lot of the problems that afflict states elsewhere, but it does not seem from this distance to be so completely chaotic as that of Pakistan.

So, why has India succeeded, albeit modestly, while Pakistan has failed? The two countries would have had similar starting conditions, being both large heavily populated multi-ethnic societies. Perhaps the organising principles of the two countries are significant, with India being set up as a secular country containing people of various religions and cultural backgrounds, while Pakistan was intended as a Muslim state (or a state for Muslims). One could argue that shared religion is actually a weak glue with which to hold a society together, contrary to what the likes of Samuel Huntington would say. Or maybe there are other material factors of which I am unaware.

On current events in particular… before Musharraf's latest autogolpe, there was an interesting article in the London Review of Books on Pakistan by Tariq Ali ("Pakistan at Sixty"). Ali is the kind of leftist writer whose work you have to be careful with, but I was very struck by some of the points he made. Over the last year, the Pakistani regime has had some face-offs with Jihadi Islamists, and also with members of the legal profession, following an earlier attempt to remove the Chief Justice from office. Contrary to what you might assume, however, it was the attempt to crack down on judicial freedom that excited the most public reaction in Pakistan, with the legal profession spearheading mass demonstrations in many Pakistani cities. The lawyers have been at the forefront of attempts to stop Musharraf's latest plot, with Pakistan's lazy politicians largely following in the rear but nevertheless finding themselves swept into the strugge by public outrage. This is perhaps a hopeful sign, in a country where lawyers have previously been only too happy to roll over whenever it suited their military rulers.

Shooting the Messenger

Shaul Mofaz, Deputy Prime Minister of Israel, has called for the sacking of International Atomic Energy Agency head, Mohammed ElBaradei . Mr ElBaradei has reported that there is no immediate prospect of Iran developing a nuclear weapon or evidence that it is trying to do so. The Israeli leadership would like Mr ElBaradei to report that Iran is close to building nuclear weapons, as this could trigger US military action against the Islamic Republic.

Mr ElBaradei is no stranger to controversy. Prior to the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, he was criticised for reporting that the Iraqi nuclear weapons programme was non-existent. No evidence for Saddam Hussein possessing a nuclear weapons programme has yet been found by Iraq's occupiers.

Unlike Iran, Israel is not a signatory to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. Israel is the only nuclear-armed state in the Middle East.

Mr ElBaradei is no stranger to controversy. Prior to the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, he was criticised for reporting that the Iraqi nuclear weapons programme was non-existent. No evidence for Saddam Hussein possessing a nuclear weapons programme has yet been found by Iraq's occupiers.

Unlike Iran, Israel is not a signatory to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. Israel is the only nuclear-armed state in the Middle East.

10 November, 2007

Fascists are rubbish

Every so often fascists from across Europe try to get together to promote shared ultra-right wing values. One factor that bedevils such projects is constant argument over which of Europe's nations is the actual master race. I recall reading  anecdotally of some gathering of Fascist meatheads that descended into an all-in swedgefest in which the various master races attempted to settle the issue with their fists.

anecdotally of some gathering of Fascist meatheads that descended into an all-in swedgefest in which the various master races attempted to settle the issue with their fists.

More recently, various far rightist parties have managed to gain more than no support at the ballot box. As well as having some representation at the national level in several European countries, they have managed to get some people elected to the European Parliament. The rules of that body give extra privileges to parliamentary groups whose members are drawn from several EU states. Thus the Identity, Tradition, and Sovereignty group was formed, as various far-right nutjobs came together to campaign against immigrants and various groups they consider reprehensible.

Unfortunately, this attempt at far-right trans-national cooperation has foundered. One big problem it faces is that the European Union is so big now that many people in the older member states now hold unsavoury racist attitudes towards people from the newer states, with far-right parties reflecting these opinions. In Italy, there is a bit of a flap on about immigrants from Romania, as a person from Romania living there recently committed a crime (Italian nationals never commit crimes). Prominent Italian fascist MEP Alessandra Mussolini has caused dismay among her Romanian colleagues by proclaiming that Romanians were "habitual law-breakers". She also caused great offence to her allies in the Greater Romania Party by saying that Italians see little difference between Romanians and members of the Roma community.

Mussolini's comments have led the Romanian MEPs threatening to withdraw from the Identity, Tradition, and Sovereignty group, leaving it below the level that would allow it to qualify as a European Parliament group.

Alessandra Mussolini is no stranger to controversy. The former topless model resigned from the allegedly post-fascist Alleanza Nazionale in 2003, after its leader visited Israel, described Fascism as "the absolute evil", and denounced the racial laws introduced by her grandfather. She had previously ran unsuccessfully for leadership of the party, when its leader had declared himself no longer a supporter of Benito Mussolini's rubbish dictatorship.

The picture comes from the BBC News article "EU far-right bloc faces collapse"

anecdotally of some gathering of Fascist meatheads that descended into an all-in swedgefest in which the various master races attempted to settle the issue with their fists.

anecdotally of some gathering of Fascist meatheads that descended into an all-in swedgefest in which the various master races attempted to settle the issue with their fists.More recently, various far rightist parties have managed to gain more than no support at the ballot box. As well as having some representation at the national level in several European countries, they have managed to get some people elected to the European Parliament. The rules of that body give extra privileges to parliamentary groups whose members are drawn from several EU states. Thus the Identity, Tradition, and Sovereignty group was formed, as various far-right nutjobs came together to campaign against immigrants and various groups they consider reprehensible.

Unfortunately, this attempt at far-right trans-national cooperation has foundered. One big problem it faces is that the European Union is so big now that many people in the older member states now hold unsavoury racist attitudes towards people from the newer states, with far-right parties reflecting these opinions. In Italy, there is a bit of a flap on about immigrants from Romania, as a person from Romania living there recently committed a crime (Italian nationals never commit crimes). Prominent Italian fascist MEP Alessandra Mussolini has caused dismay among her Romanian colleagues by proclaiming that Romanians were "habitual law-breakers". She also caused great offence to her allies in the Greater Romania Party by saying that Italians see little difference between Romanians and members of the Roma community.

Mussolini's comments have led the Romanian MEPs threatening to withdraw from the Identity, Tradition, and Sovereignty group, leaving it below the level that would allow it to qualify as a European Parliament group.

Alessandra Mussolini is no stranger to controversy. The former topless model resigned from the allegedly post-fascist Alleanza Nazionale in 2003, after its leader visited Israel, described Fascism as "the absolute evil", and denounced the racial laws introduced by her grandfather. She had previously ran unsuccessfully for leadership of the party, when its leader had declared himself no longer a supporter of Benito Mussolini's rubbish dictatorship.

The picture comes from the BBC News article "EU far-right bloc faces collapse"

BOOKS ABOUT THE MIDDLE EAST: "The Iron Wall: Israel and the Arab World" by Avi Shlaim

Before discussing the book itself, I need to quickly talk about the Israeli New Historians. These fellows set themselves the task of approaching their country's history the way historians are meant to – by looking at documents and the historical record to establish what had actually occurred in the past, rather than by simply regurgitating self-serving national myths. In a young country like Israel, with a carefully cultivated narrative around its founding, this kind of approach proved rather contentious, uncovering as it did events and counter-narratives that many would prefer to see forever buried.

Avi Shlaim is one of these New Historian people. His back academic work was the book "Collusion Across The Jordan", about the then largely obscured negotiations between the Israeli leaders and King Abdullah of Jordan around the time of the Israeli state's founding. "The Iron Wall" is a more general work, covering the relationship between the Israeli state and the Arab World; in this context, the Arab World includes both the various Arab states as well as the Palestinian people living inside what became Israel and in the territories it came to occupy. In time, the book covers the period from the foundation of the Zionist community in Palestine in the early 20th century to the election of Ehud Barak as prime minister in 1999. At this stage of the game the book cries out for a second edition, given subsequent events and the rather naïve note of optimism on which the book ends.

Shlaim's book takes its title from an article written in 1923 by Ze'ev Jabotinsky. Jabotinsky was committed to the establishment of a Jewish state in what was then Palestine, but he acknowledged a key obstacle to the project – the Arab majority population in Palestine (and, the Arabs generally beyond the territory's borders). Other Zionist leaders had fudged the issue of what to do with these people and how the emerging Jewish state would deal with them. Jabotinsky called a spade a spade, and foresaw that as the Israeli project advanced the Arabs would increasingly resist their expropriation. Jabotinsky argued that attempts to conciliate or negotiate with the Arabs were pointless, at least initially, as their wish would be to destroy the Zionist colonies and re-establish their authority in the country. Jabotinsky proposed instead to erect a metaphorical "Iron Wall" of military might around the Zionist project. Eventually the Arabs would realise that this Iron Wall was unbreakable, that the Israelis could not be defeated, and then it would be possible for the Zionists to negotiate with them and reach some sort of accommodation (that would presumably see them permanently reduced to second class citizenship or some such status).

Jabotinsky remained an oppositional figure within Zionism, but Shlaim's assertion is that his Iron Wall doctrine became the established model on the Israeli side for dealing with the Arabs. Shlaim sees this in the tendency of the Israeli state for much of its history to make early resorts to force and to happily choose escalation over the defusing of tensions. Part of Shlaim's argument, though, is that successive Israeli leaders have had a less sophisticated understanding of the idea than Jabotinsky himself, in that they have failed to register that the Iron Wall has done its job and convinced the Arab World of Israeli permanence, in that the Israeli state has been slow to pick up on opportunities to pursue negotiations and non-violent options with its neighbours.

OK, so that is the theoretical underpinning of the book. What you actually get when you read it is an account of Arab-Israeli relations based on documentary research and interviews with many leading figures. The story is mostly told from the Israeli point of view, probably because of the difficulties an Israeli researcher (or indeed anyone) would have consulting archives or conducting serious research in most Arab states. It is basically an account of interstate politics in the Middle East, from an Israeli point of view. The Israeli point of view is one of perspective rather than sympathy, however, in that Shlaim is not an apologist for his government's actions. He does not gloss over situations where Israel appears to be in the wrong, and where he feels the situation warrants it he is happy to criticise Israeli actions (one criticism sometimes made of this book is that it is too critical of Israel).

The section of this book I found most interesting was the one dealing with Israel in the 1950s, perhaps because I am more familiar with the later periods. In this period, after Israel had won the war that led to its formation, the Israeli state is generally seen as being surrounded by enemies hell-bent on its destruction, but Shlaim argues that this perspective is somewhat illusory and one deliberately cultivated. He suggests that this period was one in which Israeli leaders, wedded to the militarist ideas of Jabotinsky, missed numerous opportunities to move Middle Eastern politics onto a more pacific course. He talks in particular about various back-door negotiation channels open in the early 1950s with Nasser and about how countries, ultimately buried by an Israeli raid against an Egyptian military position (in retaliation against an attack on Israelis by Palestinians). He also asserts that Jordanian and Syrian posturing against Israel was reactive, whereas Israel was always keen to escalate any encounters.

And so it goes. While the section on the 1950s was the most interesting to me, I reckon that anyone with a beginner's interest to the Middle East would find all of this book very interesting. One thing, though, that I would like to read is a more pro-Israel book, albeit one written subsequent to this and to the work of the New Historians – that is to say, a book which is still putting a pro-Israel slant on events, even if, unlike earlier books, it is not just ignoring or explaining away events that do not fit its narrative. Can anyone recommend me such a work?

The Iron Wall also features a fascinating photo of Kissinger leering at Leah Rabin.

Avi Shlaim is one of these New Historian people. His back academic work was the book "Collusion Across The Jordan", about the then largely obscured negotiations between the Israeli leaders and King Abdullah of Jordan around the time of the Israeli state's founding. "The Iron Wall" is a more general work, covering the relationship between the Israeli state and the Arab World; in this context, the Arab World includes both the various Arab states as well as the Palestinian people living inside what became Israel and in the territories it came to occupy. In time, the book covers the period from the foundation of the Zionist community in Palestine in the early 20th century to the election of Ehud Barak as prime minister in 1999. At this stage of the game the book cries out for a second edition, given subsequent events and the rather naïve note of optimism on which the book ends.

Shlaim's book takes its title from an article written in 1923 by Ze'ev Jabotinsky. Jabotinsky was committed to the establishment of a Jewish state in what was then Palestine, but he acknowledged a key obstacle to the project – the Arab majority population in Palestine (and, the Arabs generally beyond the territory's borders). Other Zionist leaders had fudged the issue of what to do with these people and how the emerging Jewish state would deal with them. Jabotinsky called a spade a spade, and foresaw that as the Israeli project advanced the Arabs would increasingly resist their expropriation. Jabotinsky argued that attempts to conciliate or negotiate with the Arabs were pointless, at least initially, as their wish would be to destroy the Zionist colonies and re-establish their authority in the country. Jabotinsky proposed instead to erect a metaphorical "Iron Wall" of military might around the Zionist project. Eventually the Arabs would realise that this Iron Wall was unbreakable, that the Israelis could not be defeated, and then it would be possible for the Zionists to negotiate with them and reach some sort of accommodation (that would presumably see them permanently reduced to second class citizenship or some such status).

Jabotinsky remained an oppositional figure within Zionism, but Shlaim's assertion is that his Iron Wall doctrine became the established model on the Israeli side for dealing with the Arabs. Shlaim sees this in the tendency of the Israeli state for much of its history to make early resorts to force and to happily choose escalation over the defusing of tensions. Part of Shlaim's argument, though, is that successive Israeli leaders have had a less sophisticated understanding of the idea than Jabotinsky himself, in that they have failed to register that the Iron Wall has done its job and convinced the Arab World of Israeli permanence, in that the Israeli state has been slow to pick up on opportunities to pursue negotiations and non-violent options with its neighbours.

OK, so that is the theoretical underpinning of the book. What you actually get when you read it is an account of Arab-Israeli relations based on documentary research and interviews with many leading figures. The story is mostly told from the Israeli point of view, probably because of the difficulties an Israeli researcher (or indeed anyone) would have consulting archives or conducting serious research in most Arab states. It is basically an account of interstate politics in the Middle East, from an Israeli point of view. The Israeli point of view is one of perspective rather than sympathy, however, in that Shlaim is not an apologist for his government's actions. He does not gloss over situations where Israel appears to be in the wrong, and where he feels the situation warrants it he is happy to criticise Israeli actions (one criticism sometimes made of this book is that it is too critical of Israel).

The section of this book I found most interesting was the one dealing with Israel in the 1950s, perhaps because I am more familiar with the later periods. In this period, after Israel had won the war that led to its formation, the Israeli state is generally seen as being surrounded by enemies hell-bent on its destruction, but Shlaim argues that this perspective is somewhat illusory and one deliberately cultivated. He suggests that this period was one in which Israeli leaders, wedded to the militarist ideas of Jabotinsky, missed numerous opportunities to move Middle Eastern politics onto a more pacific course. He talks in particular about various back-door negotiation channels open in the early 1950s with Nasser and about how countries, ultimately buried by an Israeli raid against an Egyptian military position (in retaliation against an attack on Israelis by Palestinians). He also asserts that Jordanian and Syrian posturing against Israel was reactive, whereas Israel was always keen to escalate any encounters.

And so it goes. While the section on the 1950s was the most interesting to me, I reckon that anyone with a beginner's interest to the Middle East would find all of this book very interesting. One thing, though, that I would like to read is a more pro-Israel book, albeit one written subsequent to this and to the work of the New Historians – that is to say, a book which is still putting a pro-Israel slant on events, even if, unlike earlier books, it is not just ignoring or explaining away events that do not fit its narrative. Can anyone recommend me such a work?

The Iron Wall also features a fascinating photo of Kissinger leering at Leah Rabin.

27 October, 2007

Biofuel Madness

I am not the first person to think that farming crops not for food but to provide fuel for car driving First World cockfarmers is the path of madness. Jean Ziegler, UN rapporteur on the right to food, goes further, judging it a crime against humanity. The rush to biofuel production is pushing up the price of basic foodstuffs, creating the possibility for a worldwide humanitarian disaster. According to the BBC, even the IMF is warning against the use fo grain as car fuel.

More: Biofuels 'crime against humanity'

More: Biofuels 'crime against humanity'

14 October, 2007

BOOKS ABOUT THE MIDDLE EAST: "A History of the Middle East" by Peter Mansfield

NEW SERIES. People are often confused about the Middle East. To help them, I am going to recommend three books that people should read if they want to get a better handle on the region. I will also mention a couple more books that people might find interesting if they want to explore the area in more detail.

I should mention one thing – the term "Middle East" is these days somewhat contested. Following the publication of Edward Said's book "Orientalism", there has been much more self-criticism in the West of how other parts of the world are written about. Some consider that referring to a region as the Middle East defines it by its relationship to the West as an Other, objectifying the region and its people; as against that, one could of course say that the term "the West" defines Europe and North America by their relationship to people further to the east. A variety of circumlocutions are sometimes used to try and replace the Middle East term. These include "The Arab World", "West Asia", the horrible acronym "MENA", and so on. They are all, in their own way, rubbish, so for want of anything better, I am going to stick with referring to the region as the Middle East, as does my first book.

My first book is in fact "A History of the Middle East" by Peter Mansfield. Mansfield, now deceased, was an interesting fellow. He started his career in the British Foreign Office, but resigned in protest over Suez*, thereafter making his living as a journalist and writer. His book is, as the title suggests, a history of the region, from the dawn of time to the present day. Mansfield's triumph is to have written a relatively short book that is very easy to read and that feels always like it is telling you just enough so that you know the key aspect of what it is covering without being buried in extraneous detail.

The edition I have of this book was written in 1991. Since his death in 1996, the book has been revised again by some other bloke, though it has not been brought into the post-Saddam Hussein era yet. Nevertheless, if you want an overview of the Middle East, this is the book for you.

I also recommend "The Arabs", another book by Mansfield. This provides a history of the specifically Arab World, and then profiles each individual Arab country.

*if you don't know what I mean here by Suez then you should read this book

I should mention one thing – the term "Middle East" is these days somewhat contested. Following the publication of Edward Said's book "Orientalism", there has been much more self-criticism in the West of how other parts of the world are written about. Some consider that referring to a region as the Middle East defines it by its relationship to the West as an Other, objectifying the region and its people; as against that, one could of course say that the term "the West" defines Europe and North America by their relationship to people further to the east. A variety of circumlocutions are sometimes used to try and replace the Middle East term. These include "The Arab World", "West Asia", the horrible acronym "MENA", and so on. They are all, in their own way, rubbish, so for want of anything better, I am going to stick with referring to the region as the Middle East, as does my first book.

My first book is in fact "A History of the Middle East" by Peter Mansfield. Mansfield, now deceased, was an interesting fellow. He started his career in the British Foreign Office, but resigned in protest over Suez*, thereafter making his living as a journalist and writer. His book is, as the title suggests, a history of the region, from the dawn of time to the present day. Mansfield's triumph is to have written a relatively short book that is very easy to read and that feels always like it is telling you just enough so that you know the key aspect of what it is covering without being buried in extraneous detail.

The edition I have of this book was written in 1991. Since his death in 1996, the book has been revised again by some other bloke, though it has not been brought into the post-Saddam Hussein era yet. Nevertheless, if you want an overview of the Middle East, this is the book for you.

I also recommend "The Arabs", another book by Mansfield. This provides a history of the specifically Arab World, and then profiles each individual Arab country.

*if you don't know what I mean here by Suez then you should read this book

13 October, 2007

Oh, those South Ossetians!

Lifting a story from Popbitch, the BBC reports that the government of Georgia have recruited disco stars Boney M to the struggle against South Ossetian separatism: Boney M play on Georgia frontline

Lifting a story from Popbitch, the BBC reports that the government of Georgia have recruited disco stars Boney M to the struggle against South Ossetian separatism: Boney M play on Georgia frontlineWhat is happening is this: Boney M are going to play a concert in Tamarasheni, a small village in South Ossetia that has remained loyal to Georgia. The village is in walking distance of Tskhinvali, the rebel capital. The hope is that many South Ossetians will come to the free concert, get down to the sounds of Boney M (whose hits include "Rasputin", "Daddy Cool", "Ma Baker", and "By The Rivers of Babylon"). They will then start to realise that life will be "better and more fun if they returned to government control". An unnamed Georgian official is quoted as saying that "peaceful life resumes when people sing songs".

Boney M have some experience of dealing with the problems of conflict. Their 1977 hit "Belfast", was a plea for peace in that troubled city. The band's own experience illusrates the dangers of separatism, as there are now two mutually hostile Boney M touring bands. It is not known which one is playing the concert in Georgia.

As an aside, the BBC correspondent in Georgia is one Matthew Collin, co-author or sole author of interesting books such as "Altered State" (about Ecstasy culture and dance music) and "Serbia Calling" (about Radio B-92 and the Serbian counter culture under Milosevic).

EDIT: that BBC article has been updated. The concert has taken place and was attended by many people. The Boney M that played was fronted by Marica Barrett, one of the original members of the band. There are at least two other bands with original members touring as Boney M.

Aghanistan Realpolitik

A piece by Philip Jakeman on openDemocracy suggests that there is a real prospect of Taliban leader Mohammed Omar joining the government of Hamid Karzai: Afghanistan: necessity and impossibility

Many would of course consider this a less than ideal outcome, as the Taliban are infamous for the human rights abuses they perpetrated as rulers of Afghanistan. Jakeman points out, however, that many members of Karzai's current government are themselves notorious gangsters and human rights abusers. The Taliban retain a considerable following, and brining them into the government might lead to the country's pacification. The USA is reportedly considering the idea, notwithstanding the $10,000,000 bounty it has on the head of Mohammed Omar.

Many would of course consider this a less than ideal outcome, as the Taliban are infamous for the human rights abuses they perpetrated as rulers of Afghanistan. Jakeman points out, however, that many members of Karzai's current government are themselves notorious gangsters and human rights abusers. The Taliban retain a considerable following, and brining them into the government might lead to the country's pacification. The USA is reportedly considering the idea, notwithstanding the $10,000,000 bounty it has on the head of Mohammed Omar.

11 October, 2007

Yet more Genocide

If you can't get enough of the mass killing, there is an interesting article by Ben Kiernan on the subject on openDemocracy: Blood and soil: the global history of genocide

Armenia, 1915

I think it is in Robert Fisk's Pity The Nation: Lebanon at War that an odd feature of the Armenian genocide is mentioned. Ottoman Turkey was at the time an ally of the German Empire, and there were a large number of German troops stationed in the Turkish Empire to assist their allies. Fisk wonders if any junior officers lent a helping hand to the elimination of the Armenians from Eastern Anatolia, coming home with some top tips they could apply in Europe just under 30 years later.

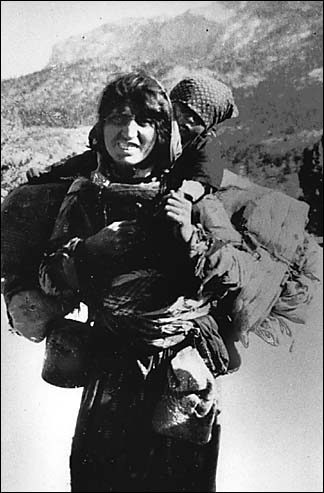

I think it is in Robert Fisk's Pity The Nation: Lebanon at War that an odd feature of the Armenian genocide is mentioned. Ottoman Turkey was at the time an ally of the German Empire, and there were a large number of German troops stationed in the Turkish Empire to assist their allies. Fisk wonders if any junior officers lent a helping hand to the elimination of the Armenians from Eastern Anatolia, coming home with some top tips they could apply in Europe just under 30 years later.One German officer who was in Turkey at the time was Armin T. Wegner. Rather than assist in the extermination of the Armenians, he did his utmost to prevent further massacres and worked tirelessly to publicise the horrors that Enver Pasha's government was perpetrating. As well as collecting and disseminating documents on the massacres, Wegner took numerous photos of Armenian deportees and of the corpses of the genocide's victims; if you have seen any black and white pictures of corpses or desperate Armenians in the media over the last few days, they were almost certainly taken by him.

Wegner lived until the late 1970s, though he did spend some time in concentration camps during the Third Reich period. He was apparently the only German writer to publicly denounce anti-Jewish measures introduced by the Nazis in 1933.

You can see some of Wegner's pictures here: Armenian Deportees: 1915-1916

Massacres and Genocide

The Foreign Affairs Committee of the United States House of Representatives has voted to recognise the 1915 massacres of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire as genocide. The Turkish government (and, in all likelihood, Turkish people generally) are very annoyed. There are suggestions that this might have terrible repercussions regarding US efforts to pacify Iraq.

People who deny the extermination of Jewish people by the Nazis in the Second World War typically say that there was no targetted programme of mass killing and that the numbers who died are grossly exaggerated and no higher than might be expected in a continent at war. Armenian genocide denial is somewhat similar. In fairness to the Turks, my understanding is that they do not deny that very large numbers of Armenians were killed by agents of the Ottoman Empire during the First World War, or that many of these victims may well have been non-combatants. I don't know if they accept the widely accepted estimate of 1,500,000 victims, but I think they agree that the numbers were very large. The Turks also talk, however, about Turkish and people of other ethnicities (e.g. Kurds) killed by Armenian rebels and so on, though I doubt they seriously claim that massacares of Turks and Kurds by Armenians were in the same order of magnitude as killings of Armenians by Kurds and Turks.

My understanding of the Turkish position is that they take exception to the word genocide, with its connotations of systematic and deliberate extermination. They point out that many Armenians in areas of the Ottoman Empire other than Eastern Anatolia (e.g. Istanbul itself) were not exterminated en masse (though they were subject to considerable persecution), suggesting that the regime was not hell-bent on the total elimination of Armenians. Analysis of the history of the first world war does, however, make plain that the Turkish leadership under Enver Pasha were determined to expel all Armenians from Eastern Anatolia, and were not too bothered if very few of the expellees failed to arrive at their expulsion destination if not actively determined to exterminate them all. I don't know if there is documentary evidence to prove a centrally directed campaign of mass murder, but the balance of probability certainly supports the idea that such was the regime's goal.

My own feeling is that genocide has become an overly emotive word, something like terrorism in that it is thrown at whoever you don't like this week. I don't think, however, that the Turkish government is doing itself any favours on this issue; their endless carping on definitions makes them look like a shifty plea bargainers. That said, pressurising Turkey on this point does not obviously seem to serve any purpose other than to strengthen the country's reactionary nutjobs, whose current project is to invade Iraqi Kurdistan.

The BBC has an interesting article on the history of Turkish attitudes to the Armenian mass killings: Turkey's Armenian dilemma

some of what I have written here is rehashed from a comment here. This has been crossposted to The Dublin School of International Relations.

People who deny the extermination of Jewish people by the Nazis in the Second World War typically say that there was no targetted programme of mass killing and that the numbers who died are grossly exaggerated and no higher than might be expected in a continent at war. Armenian genocide denial is somewhat similar. In fairness to the Turks, my understanding is that they do not deny that very large numbers of Armenians were killed by agents of the Ottoman Empire during the First World War, or that many of these victims may well have been non-combatants. I don't know if they accept the widely accepted estimate of 1,500,000 victims, but I think they agree that the numbers were very large. The Turks also talk, however, about Turkish and people of other ethnicities (e.g. Kurds) killed by Armenian rebels and so on, though I doubt they seriously claim that massacares of Turks and Kurds by Armenians were in the same order of magnitude as killings of Armenians by Kurds and Turks.

My understanding of the Turkish position is that they take exception to the word genocide, with its connotations of systematic and deliberate extermination. They point out that many Armenians in areas of the Ottoman Empire other than Eastern Anatolia (e.g. Istanbul itself) were not exterminated en masse (though they were subject to considerable persecution), suggesting that the regime was not hell-bent on the total elimination of Armenians. Analysis of the history of the first world war does, however, make plain that the Turkish leadership under Enver Pasha were determined to expel all Armenians from Eastern Anatolia, and were not too bothered if very few of the expellees failed to arrive at their expulsion destination if not actively determined to exterminate them all. I don't know if there is documentary evidence to prove a centrally directed campaign of mass murder, but the balance of probability certainly supports the idea that such was the regime's goal.

My own feeling is that genocide has become an overly emotive word, something like terrorism in that it is thrown at whoever you don't like this week. I don't think, however, that the Turkish government is doing itself any favours on this issue; their endless carping on definitions makes them look like a shifty plea bargainers. That said, pressurising Turkey on this point does not obviously seem to serve any purpose other than to strengthen the country's reactionary nutjobs, whose current project is to invade Iraqi Kurdistan.

The BBC has an interesting article on the history of Turkish attitudes to the Armenian mass killings: Turkey's Armenian dilemma

some of what I have written here is rehashed from a comment here. This has been crossposted to The Dublin School of International Relations.

10 October, 2007

The War on Rhode Island

openDemocracy has also been running a number of article about deliberative democracy, partly in the context of more advanced opinion polling and partly as a way of actually making political decisions. Deliberative democracy is where you grab some people at random. With normal opinion polling you would just ask them a load of questions, often effectively generating instant opinions, but what you do with the deliberative approach is you make them read up on a load of issues and debate them among themselves and then you make them decide an outcome. I suppose the jury system is a bit like this. This kind of random choosing of people to make decisions was used in ancient Athens; as a classicist I am therefore all for it.

However, I only really bring the subject up to mention an vignette contained in an article by James Fishkin. He talks about how Rhode Island was the only one of the original members of the United States of America to have a referendum on the constitution. The electorate voted against, incensing the federalists who argued that a referendum (unlike an elected consitutional convention) could not produce a truly deliberated result. The governments of Connecticut and Massachusetts were so incensed that they threatened to invade , leading to Rhode Island convening a convention that opted to join the Union after all.

I wonder would it be possible to invade the United Kingdom, to oblige them to accept the EU Consitution and the Euro?

However, I only really bring the subject up to mention an vignette contained in an article by James Fishkin. He talks about how Rhode Island was the only one of the original members of the United States of America to have a referendum on the constitution. The electorate voted against, incensing the federalists who argued that a referendum (unlike an elected consitutional convention) could not produce a truly deliberated result. The governments of Connecticut and Massachusetts were so incensed that they threatened to invade , leading to Rhode Island convening a convention that opted to join the Union after all.

I wonder would it be possible to invade the United Kingdom, to oblige them to accept the EU Consitution and the Euro?

Palestine: Armed Struggle v. Mass Resistance

The fundamental problem with openDemocracy is that reading long articles about anything on a screen is a complete pain, regardless of how interesting they are. Nevertheless, they publish much that is worth reading, for all that I would rather read it in a print periodical. One interesting piece is an article by Maria Stephan on proposals within Palestinian society to move the national struggle from the vanguardist mode of lethal violence to one of mass struggle based around collective action and the use of non-lethal force. She points out the obvious - that these methods yielded real dividends during Intifada 1, while the elitist violence of the al-Aqsa Intifada have gained dick-all. She does, however, underestimate the problems associated with a transition to non-violent mass struggle. One factor seriously discrediting this new idea is its advocates, who seem mainly to be those associated with President Mahmud Abbas and the illegal government of Salam Fayyad; their credibility as advocates of the Palestinian cause is rather limited, given the fond opinions that the USA and Israel seem to have of them. The other problem is that non-violent mass struggle is very difficult, requiring a level of organisational ability that might not be possessed by a Palestinian society wracked by years of Israeli repression. The occupiers' willingness to use lethal force against stone throwers and demonstrators played a major part in pushing the al-Aqsa Intifada away from mass action to elitist violence, and any attempt to move in that direction could easily provoke a similar response.

09 October, 2007

Europe's Shame

Am I reading this right? It seems like the US Supreme Court has basically ruled that the CIA can kidnap and torture whoever it likes, and then escape legal sanctions by claiming that the prosecution of the criminals who perpetrated these acts would compromise state security.

The article concerns Mr Khaled al-Masri, who was kidnapped by the CIA from Germany and transported to a torture camp in Afghanistan. Apparently the German government has dropped an extradition request against his kidnappers. I have already mentioned the Italian government's decision not to pursue the extradtion of a gang who kidnapped one Mr Abu Omar from their country.

There is this idea in the world that European countries somehow stand in opposition to the human rights violations of the United States. In reality, Europe (or European governments) do not care, and are happy to let US gangs kidnap and torture whoever they like. No one seems to really care about this, given the way the whole extraordinary rendition story lives only in the inside pages of the newspapers.

The article concerns Mr Khaled al-Masri, who was kidnapped by the CIA from Germany and transported to a torture camp in Afghanistan. Apparently the German government has dropped an extradition request against his kidnappers. I have already mentioned the Italian government's decision not to pursue the extradtion of a gang who kidnapped one Mr Abu Omar from their country.

There is this idea in the world that European countries somehow stand in opposition to the human rights violations of the United States. In reality, Europe (or European governments) do not care, and are happy to let US gangs kidnap and torture whoever they like. No one seems to really care about this, given the way the whole extraordinary rendition story lives only in the inside pages of the newspapers.

06 October, 2007

Desmond Tutu banned

Via Brian's Study Breaks I learn that Archbishop Desmond Tutu has had an invitation to speak at St. Thomas' University in Minneapolis/St. Paul withdrawn. It was feared that the presence of Nobel Laureate Tutu might offend those who lend Israel unqualified support.

01 October, 2007

Conference on Russia

If you live in Ireland, have ninety quid to throw away, and are interested in Russia then you could do worse than go the Royal Irish Academy's Committee for International Affairs conference on the 23rd November. The full title of the conference is Russia's Global Perspective: Defining a New Relationship with Europe and America, and if you follow the link you can see the impressive list of speakers they have. Well, the ones I have heard of are very impressive, so I assume the others are too.

From President to Prime Minister

The BBC reports that when he steps down as president, Vladimir Putin is going to run for the Russian parliament and that he aspires to become the country's prime minister. The BBC reports this as a shocking new development, though I had read this suggested in the academic literature on Russian semi-presidentialism. People have been wondering for some time whether Putin was really going to step down as president, given his obvious enjoyment of being the top dog in Russian politics. The switch to prime minister allows him to remain at the centre of politics without having to change the constitution to allow him to run for another term; and prime ministers are not bound by inconvenient term limits.

At the moment, the constitution makes the Russian prime minister clearly subservient to the president, and the BBC quotes one Andrei Ryabov of the Carnegie Moscow Center as saying that the consitution will need to be changed to allow Putin to remain the country's leader. This may or may not be the case. One thing you often see with semi-presidential systems is that the primacy of the premiership and presidency is decided not by the constitutional prerogatives of the offices, but by who occupies them. In Russia's case, Putin as prime minister will remain the man around whom politics has rotated for the last seven years. It is still not clear who Putin favours as his successor, but it should not be impossible for him to find a pliant yes-man to run for the job.

At the moment, the constitution makes the Russian prime minister clearly subservient to the president, and the BBC quotes one Andrei Ryabov of the Carnegie Moscow Center as saying that the consitution will need to be changed to allow Putin to remain the country's leader. This may or may not be the case. One thing you often see with semi-presidential systems is that the primacy of the premiership and presidency is decided not by the constitutional prerogatives of the offices, but by who occupies them. In Russia's case, Putin as prime minister will remain the man around whom politics has rotated for the last seven years. It is still not clear who Putin favours as his successor, but it should not be impossible for him to find a pliant yes-man to run for the job.

27 September, 2007

Links and Categories

If you are reading Hunting Monsters, look to the right. I have tidied the categories somewhat and updated my links.

Regarding links, I have decided to delete all links to blogs that do not have serious IR content, even if they link to me. Some of the ones there are only just hanging in, but as Hunting Monsters does not really have a major IR content these days I can afford to be generous.

Regarding links, I have decided to delete all links to blogs that do not have serious IR content, even if they link to me. Some of the ones there are only just hanging in, but as Hunting Monsters does not really have a major IR content these days I can afford to be generous.

It's later than you think

Student harangues politician; student is then dragged from the meeting by policemen, subjected to electrical shocks, and charged with trying to incite a riot.

This was in the United States of America. The incident is reminiscent of the bundling out of a Labour Party conference in 2005 of a delegate who heckled the then foreign secretary (and his subsequent detention under anti-terrorism legislation when he tried to re-enter the hall).

This was in the United States of America. The incident is reminiscent of the bundling out of a Labour Party conference in 2005 of a delegate who heckled the then foreign secretary (and his subsequent detention under anti-terrorism legislation when he tried to re-enter the hall).

12 September, 2007

My Inner Librarian

I have attached keyword labels to all Hunting Monsters posts, and put these labels to the right on the Hunting Monsters front page. The next step is to rationalise these keywords.

Pot. Kettle.

"He's a man who is a propagandist and is not a scholar."

Thus speaks Alan Dershowitz, who when not advocating the legalisation of torture, is a man always ready to heap vitriol on anyone with whom he disagrees. He was commenting on the recent resignation from DePaul University of Norman Finkelstein. DePaul had previously denied Finkelstein tenure, following a campaign against him by Dershowitz. The Dershowitz-Finkelstein love-in has being going on for a while now, with Finkelstein's recent book Beyond Chutzpah being largely a riposte to Dershowitz's The Case For Israel. Part of Finkelstein's claim was that Dershowitz had plagiarised elements of his book from Joan Peters' From Time Immemorial; Finkelstein had originally made his representation by exposing that book as fraudulent and plagiarised.

I can't claim any great familiarity with Finkelstein's work, nor can I comment in an informed manner on his suitability for tenure in DePaul. My suspicion, though, is that Finkelstein is being punished not for unscholarly writing but for taking on one of the giants of his profession, and that he was denied tenure not on academic grounds but because he was trouble.

Thus speaks Alan Dershowitz, who when not advocating the legalisation of torture, is a man always ready to heap vitriol on anyone with whom he disagrees. He was commenting on the recent resignation from DePaul University of Norman Finkelstein. DePaul had previously denied Finkelstein tenure, following a campaign against him by Dershowitz. The Dershowitz-Finkelstein love-in has being going on for a while now, with Finkelstein's recent book Beyond Chutzpah being largely a riposte to Dershowitz's The Case For Israel. Part of Finkelstein's claim was that Dershowitz had plagiarised elements of his book from Joan Peters' From Time Immemorial; Finkelstein had originally made his representation by exposing that book as fraudulent and plagiarised.

I can't claim any great familiarity with Finkelstein's work, nor can I comment in an informed manner on his suitability for tenure in DePaul. My suspicion, though, is that Finkelstein is being punished not for unscholarly writing but for taking on one of the giants of his profession, and that he was denied tenure not on academic grounds but because he was trouble.

Roundup

Roundup is a potentially interesting new blog, in which some Tracer Hand fellow comments on stuff going on in the world. I will add it to Hunting Monsters' links if it does not prove timewaster.

The most recent post is about Pantsyr... I wonder are they anything to do with Manpads?

The most recent post is about Pantsyr... I wonder are they anything to do with Manpads?

08 September, 2007

Farewell Spy School

I have handed in my thesis.

Now I just need to find a job with one of the world's more forward thinking intelligence services.

Now I just need to find a job with one of the world's more forward thinking intelligence services.

Now I just need to find a job with one of the world's more forward thinking intelligence services.

Now I just need to find a job with one of the world's more forward thinking intelligence services.

02 September, 2007

Lolcountry

More on Belgium: Belgium doomed?. Nicholas reckons that Belgium will survive the current crisis but has possibly terminal problems in the long run, as all the old hands from pre-federal days who broker compromises are coming to the end of their lives.

One great thing about Belgium is that the country has an east-west orientation, but the national divide runs on a north-south axis. So if Belgium splits in two we will be left with two long and thin comedy countries.

I hope Belgium does not split up, as I have a sentimental fondness for the place, based on it being a country of comics, rich food, and tasty beer. Its weirdo dysfunctionality is also appealing in an I'm-glad-I-don't-live-there kind of way. I also like the way Belgians are all very clear that regardless of what language they speak, they are neither Dutch nor French. I wish its leaders would cop themselves on... can't they just get along?

One great thing about Belgium is that the country has an east-west orientation, but the national divide runs on a north-south axis. So if Belgium splits in two we will be left with two long and thin comedy countries.

I hope Belgium does not split up, as I have a sentimental fondness for the place, based on it being a country of comics, rich food, and tasty beer. Its weirdo dysfunctionality is also appealing in an I'm-glad-I-don't-live-there kind of way. I also like the way Belgians are all very clear that regardless of what language they speak, they are neither Dutch nor French. I wish its leaders would cop themselves on... can't they just get along?

I need to get out more

I am reading this book by Amin Maalouf called "The Crusades Through Arab Eyes". Last night I had a great anxiety dream, about how my thesis needs a last minute change to discuss the impact of the fall of the Abbasid Caliphate on Palestinian semi-presidentialism.

01 September, 2007

Belgium To Split?

I have been reading on blogs that Belgium is about to split in two or something. Maybe they will have a huge war and FRONT 242 will reform and release a concept album about it all, just like LAIBACH did with the former Yugoslavia.

Polish elections

There are elections taking place in Poland later this year. The last elections were held only two years ago. These early elections have been triggered by the collapse of the governing coalition, with Self-Defence and The League of Polish Families dropping out of the coalition dominated by the Law & Justice party (Law & Justice is often abbreviated in English to its Polish initials, PiS).

The last round of elections saw parliamentary and presidential elections take place in a short space of time. They produced the unusual result whereby two twin brothers came to dominate Poland's politics, with Lech Kaczynski becoming the country's president and Jaroslaw Kaczynski the leader of the largest government party (and subsequently the prime minister). The Kaczynskis then proceeded to govern in a manner that appealed strongly to their natural supporters, while simultanaeously convincing many other observers of the country's politics that they are a pair of boorish fuckwits.

It is funny noticing how international sentiment turned against the twins. Around the time of their elevation, a lot of international commentators were saying things like "they may be a pair of ultra-catholic weirdos, but they do seem to be serious about stamping out the corruption and cronyism that have bedevilled Poland since the transition". Since then, these commentators have been increasingly struck by the Kaczynskis' love of picking fights with international actors (Germany, the EU, Russia) for no obvious gain except to make populist appeals to Polish public opinion. A certain amount of schadenfreude has greeted the collapse of the governing coalition and the calling of early electons, with people expecting that this will mean an end to the terrible twins. Expectations of the twins' political demise are perhaps premature. There is an interesting article by Derek Scally in today's Irish Times, suggesting that the Kaczynskis remain popular with a large section of the Polish population. PiS could still poll strongly in the election, particularly if the vote turns into a highly polarised contest between PiS and a coalition led by the country's former communists. Even if PiS is hammered in the elections and a new "left" government takes office, we will not have seen the last of the Kaczynskis. Jaroslaw will no longer be prime minister, but Lech will remain as president. Polish presidents have considerable powers, and it would be interesting to see how President Kaczynski manages to deal with a hostile government.

The last round of elections saw parliamentary and presidential elections take place in a short space of time. They produced the unusual result whereby two twin brothers came to dominate Poland's politics, with Lech Kaczynski becoming the country's president and Jaroslaw Kaczynski the leader of the largest government party (and subsequently the prime minister). The Kaczynskis then proceeded to govern in a manner that appealed strongly to their natural supporters, while simultanaeously convincing many other observers of the country's politics that they are a pair of boorish fuckwits.

It is funny noticing how international sentiment turned against the twins. Around the time of their elevation, a lot of international commentators were saying things like "they may be a pair of ultra-catholic weirdos, but they do seem to be serious about stamping out the corruption and cronyism that have bedevilled Poland since the transition". Since then, these commentators have been increasingly struck by the Kaczynskis' love of picking fights with international actors (Germany, the EU, Russia) for no obvious gain except to make populist appeals to Polish public opinion. A certain amount of schadenfreude has greeted the collapse of the governing coalition and the calling of early electons, with people expecting that this will mean an end to the terrible twins. Expectations of the twins' political demise are perhaps premature. There is an interesting article by Derek Scally in today's Irish Times, suggesting that the Kaczynskis remain popular with a large section of the Polish population. PiS could still poll strongly in the election, particularly if the vote turns into a highly polarised contest between PiS and a coalition led by the country's former communists. Even if PiS is hammered in the elections and a new "left" government takes office, we will not have seen the last of the Kaczynskis. Jaroslaw will no longer be prime minister, but Lech will remain as president. Polish presidents have considerable powers, and it would be interesting to see how President Kaczynski manages to deal with a hostile government.

Open Democracy

People have been bigging up Open Democracy. It is one of those websites which carries articles by noted people about stuff happening in the world.

Some recent articles include:

Cyprus’s risky stalemate by Fred Halliday, a handy primer to what's been happening over the last while in Cyprus, reminding me yet again that letting (Southern) Cyprus join the EU in advance of a deal on the island was an act of most dreadful folly.

Arab Christians: a lost modernity by Tarek Osman, on the retreat of Arab Christians from the mainstream of their countries. People tend to forget how many Christians there are in the Middle East, with Egypt having a Christian population of some 15% and Syria, Palestine, Iraq, and Lebanon all having substantial and ancient Christian communities of their own.

Indonesia: the biofuel blowback by James Painter. All that biofuel shite is leading to farmers in Indonesia being kicked off their land so that car people in Europe and North America can keep on driving. Mentioned in passing is the threat to the Orangutang's continued existence by the turning of jungle into palm oil plantations.

The recurring anniversary of wilderness by Jim Gabour, an evocative article on what New Orleans is getting up to these days.

Open Democracy has its own RSS feed: http://www.opendemocracy.net/xml/rss/home/index.xml

Some recent articles include:

Cyprus’s risky stalemate by Fred Halliday, a handy primer to what's been happening over the last while in Cyprus, reminding me yet again that letting (Southern) Cyprus join the EU in advance of a deal on the island was an act of most dreadful folly.